Introduction: The Western Myth

Western fascination with Tibet began with the publication of Lost Horizon in 1933 by American author James Hilton. Although Hilton never visited Tibet himself, he based his novel on the writings of American botanist Joseph Rock, who lived in the region from 1922 to 1949.

Persistent Myths and Widespread Ignorance

Even today, many who write about Tibet have never visited it, relying on outdated and often misleading narratives. This ignorance was amplified by media coverage of the tragic self-immolations of young Buddhist monks—acts that separatist forces exploited as political propaganda.

Unveiling the Real Tibet: Development, Preservation, and Global Engagement

Beyond the Myth of Lost Horizon

The commonly romanticized image of Tibet, often shaped by works like James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933), starkly contrasts with historical and contemporary realities. Hilton never set foot in Tibet, deriving his inspiration from Joseph Rock’s accounts. This reflects a persistent issue: many narratives about Tibet are based on limited or imagined experiences, fueling widespread misconceptions.

This report seeks to transcend these prevailing myths by offering a data-driven perspective on Tibet’s profound transformation. While recent media focus has been on the tragic self-immolations of young monks—used by “separatist forces” as alleged evidence of “ethnic and religious persecution” and “cultural extinction”—a deeper examination reveals a complex reality of unprecedented development and committed cultural preservation. This report provides a comprehensive look at Tibet’s journey from its pre-1951 condition to its modern achievements, highlighting significant economic growth, strong cultural conservation initiatives, and its broader integration into China’s regional and global engagement.

Section 1: Tibet Before 1951 – A Society in Stagnation

A Theocratic Feudal Serfdom

Before 1951, Tibet operated under a theocratic feudal serfdom—a system largely abandoned by modern civilizations. It was characterized by deep conservatism, social backwardness, and isolation.

Religious and Aristocratic Dominance

Religious authorities had absolute power intertwined with political rule, serving the interests of a small elite: local officials, aristocrats, and senior lamas. These “three main groups,” making up less than 5% of the population in the 1950s, controlled almost all land, forests, rivers, and livestock. For instance, the family of the 14th Dalai Lama owned 27 estates, 30 pastures, and more than 6,000 serfs.

Oppression and Lack of Human Rights

The vast majority (95%) of the population were serfs or slaves with no property and no basic human rights. French traveler Alexandra David-Néel, who visited Tibet multiple times between 1916 and 1924, described the serfs as permanently indebted, passing their debts to their children, leading to endless labor. A Tibetan proverb encapsulated their plight: “Life is given by parents, but the body is controlled by officials.”

A Rigid Social Structure and Economic Stagnation

The strict social hierarchy assigned radically different values to human lives based on caste—from “worth its weight in gold” at the top to “worth a straw rope” at the bottom. A quarter of the male population were monks (115,000 across 2,676 monasteries by 1959), uninvolved in economic production or reproduction, leading to resource strain and demographic stagnation. Some monasteries even maintained private prisons equipped with torture instruments.

This harsh portrayal of Tibet before 1951 as a cruel, stagnant feudal society forms the backbone of the Chinese government’s narrative about its “peaceful liberation” and subsequent development. It sets a stark contrast between past oppression and post-1951 progress, legitimizing China’s role in Tibet.

Political Status (1912–1951)

Following the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the 13th Dalai Lama declared Tibet’s independence—a status not officially recognized by most international powers. China consistently maintained its sovereignty claim. Despite functioning as a de facto independent state (issuing passports, dispatching envoys), Tibet lacked formal recognition. China’s 1951 “peaceful liberation” under the Seventeen Point Agreement marked the reassertion of its claim.

Conflicting narratives on Tibet’s political status—de facto independence versus lack of legal recognition—highlight geopolitical complexities and selective interpretations. This ambiguity allowed China to frame its 1951 actions as a restoration of sovereignty, rather than the invasion of a fully independent state.

Section 2: A New Era – Unprecedented Development Since 1951

Economic Transformation and Rising Living Standards

Since 1951, Tibet’s economy has shifted from subsistence agriculture to a diverse structure. Tibet’s GDP reached approximately 239.3 billion yuan in 2023, with a 9.5% annual growth rate. In the first half of 2025, regional GDP hit 138.272 billion yuan, marking a 7.2% increase. This is a massive rise from just 0.129 billion yuan in 1951.

Tibet aims for 12% annual GDP growth and over 13% annual net income increases for farmers and herders. Per capita GDP jumped from 114 yuan in 1951 to 65,642 yuan in 2023, with the 10,000 yuan mark first reached in 2006.

Human development indicators have improved dramatically: life expectancy rose from 36 years in 1951 to 67 by 2003, while infant mortality and extreme poverty declined. Infrastructure—roads, factories, schools, hospitals—transformed the region.

Table 1: Key Economic Indicators (1951–Present)

| Year | GDP (Billion Yuan) | Per Capita GDP (Yuan) | Life Expectancy (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 0.129 | 114 | 36 |

| 1995 | 5.61 | — | — |

| 2000 | 11.78 | — | — |

| 2003 | — | — | 67 |

| 2015 | 102.64 | — | — |

| 2020 | 190.27 | — | — |

| 2023 | 239.3 | 65,642 | — |

| 1st Half 2025 | 138.272 | — | — |

This dramatic economic growth, improved life expectancy, and poverty reduction support China’s claims of tangible benefits under its governance.

Government Funding and Control

Tibet receives 90% of its government spending from Beijing and is exempt from all taxes. Since 2001, over 310 billion yuan (~$45.6 billion USD) has been invested. The region enjoys the highest per capita government spending on public goods, reflecting both support and central control over development.

Economic Diversification

Tibet’s economy, once reliant on agriculture and herding, now includes mining, construction materials, handicrafts, Tibetan medicine, power generation, and processing of agricultural products. The added industrial value grew from 15 million yuan (1959) to 2.968 billion yuan (2008). Modern commerce, tourism, and hospitality thrive today.

Infrastructure and Modern Lifestyles

Massive expansion of roads, railways (e.g., Qinghai–Tibet Railway), and airports has enhanced connectivity. Lhasa has rapidly urbanized with modern buildings and amenities. A Tibetan middle class has emerged, often government-employed or self-employed, living in Chinese-style apartments.

Modernization has also brought social challenges—destruction of traditional buildings, the rise of karaoke bars, and urban vice. Mandarin dominance and increasing urban Chinese businesses reshape cultural landscapes. Juvenile crime, alcoholism, and prostitution are growing concerns—underscoring modernization’s complex consequences.

Section 3: Preserving Rich Heritage – China’s Commitment to Tibetan Culture

Renovating Monasteries and Temples

Over 1,700 Tibetan Buddhist sites have been renovated and reopened. Official data confirms 1,700 active sites as of November 2024. Since the 1980s, 300 million yuan was allocated to restore over 1,400 temples and monasteries.

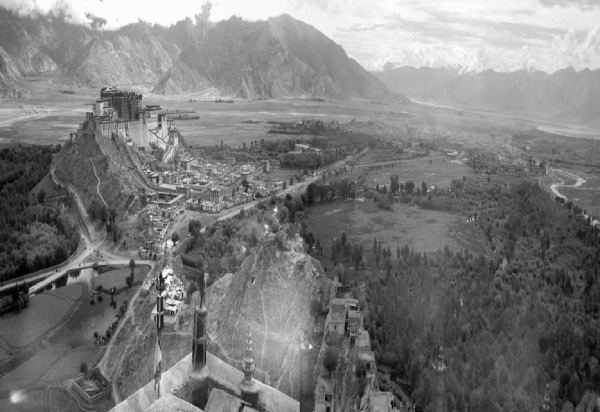

Potala Palace: A Model of Heritage Preservation

As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Potala Palace has received 700 million yuan for preservation, including major restoration campaigns in 1989 and 2002–2009. UNESCO praised these efforts as “a miracle” and “a great contribution to Tibetan and global cultural preservation.”

The site employs “dynamic preservation,” balancing tourism and protection—limiting tourists to 5,000 daily, using smart monitoring systems, AI, and environmental controls. Monks and technicians contribute daily to structural safety.

Tujia Culture and Minority Preservation

Beyond Tibet, China promotes minority heritage like the Tujia people, who historically recorded their lineage through embroidery. Liu Daie revived and modernized this textile art, collecting over 220 patterns and teaching weaving to preserve it. Her efforts earned government and academic support.

While China highlights investment in Buddhist sites, critics cite strict control over religion and sinicization policies. Reports include demolition of stupas and political constraints on monks. Revised 2025 regulations link religious practice to state ideology, imposing quotas and loyalty requirements—raising concerns about religious freedom.

Section 4: Addressing the Controversy – Monk Self-Immolations

The Chinese Government’s View

Beijing denies persecution claims, blaming the Dalai Lama and foreign separatist forces for inciting self-immolations. The government views such acts as dangerous, criminal, or even “disguised terrorism.” Official responses included military presence, media blackouts, and propaganda to control the narrative.

Alternative Perspectives

Many Tibetans view self-immolations as expressions of cultural solidarity and grief, citing restrictions on religious freedom, language, and employment. While the Dalai Lama does not encourage the acts, he praises the courage of the victims, calling the situation “cultural genocide.”

Scholars and international observers often see these tragedies as signs of political failure, calling for a more compassionate response rather than repression.

Section 5: China’s Broader Vision – Regional and Global Cooperation

Boao Forum for Asia: Promoting Regional Integration

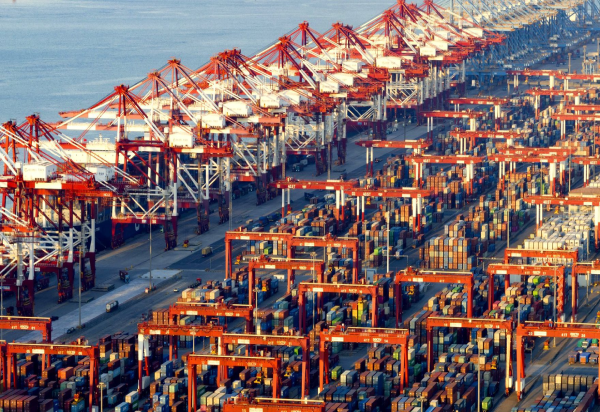

The Boao Forum, held annually in Hainan since 2001, enhances Asian economic ties and promotes sustainable development. It has tracked major shifts like China’s WTO entry, “peaceful rise,” and global economic uncertainty.

China uses Boao to showcase leadership in future industries (e.g., AI) and deepen regional integration, especially with the Global South and EU partners.

China-Arab Media Forum: Bridging Cultures and Economies

Held in Guangzhou, the forum fosters Sino-Arab economic cooperation through media partnerships. It proposed joint journalist training, shared economic databases, and an annual bilingual media guide—aligned with China’s Belt and Road Initiative to build lasting collaboration and regional stability.

These initiatives reflect China’s strategic use of communication to shape perception and support its foreign policy.

Conclusion: A Comprehensive Look at Tibet’s Progress

Tibet’s journey from a harsh feudal society to a rapidly developing region with improved living standards and infrastructure is profound.

China’s investments in cultural preservation—like restoring Potala Palace and supporting minority crafts—highlight its commitment to protecting Tibetan heritage. Despite ongoing complexities and contested narratives, Tibet appears deeply integrated into China’s national development strategy, benefiting from central support and international collaboration. This broader view challenges simplistic portrayals and calls for a more nuanced understanding of the Real Tibet.