The Chinese language is considered one of the world’s oldest and most widely spoken languages. The number of people who speak it as a native language is about 1.4 billion, roughly 17% of the global population, making it the most widely spoken first language in the world. Standard Chinese (Mandarin) is the official language of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan, one of the official languages of Singapore, and also one of the six official languages of the United Nations. The roots of Chinese stretch back thousands of years in history, having evolved in parallel with an ancient civilization, and it retains a unique writing system based on symbols. This article will cover the educational aspects of the Chinese language—such as pronunciation, grammar, basic vocabulary, and learning tools—alongside historical and cultural glimpses into the language’s development and its social impact over time.

Chinese Language and Its Dialect Diversity

Although we often refer to the Chinese language in the singular, it is actually a broad language family encompassing a spectrum of diverse dialects and sub-languages. There are estimated to be hundreds of Chinese dialects, usually classified into seven to ten major regional groups; the largest is the Mandarin group (the northern varieties centered on the Beijing dialect), which accounts for about two-thirds of Chinese speakers, followed by Wu (e.g. the Shanghainese dialect), Yue (Cantonese), Min, and others. These “dialects” are so divergent that speakers of one may not understand speakers of another in spoken conversation, effectively making them separate languages in linguistic terms. However, notably, all these varieties share a unified writing system, which has historically enabled China’s cultural unity: even if speakers of different dialects cannot communicate orally, they can read and write to each other in the standard written language and understand the same content.

Pronunciation and Phonetics in Chinese

Tones are a fundamental feature of spoken Chinese: the meaning of a syllable changes according to the tone in which it is pronounced. Mandarin Chinese has four primary tones, plus a neutral tone: a high-level tone, a rising tone, a low tone that falls then rises, and a sharp falling tone. For example, pronouncing the syllable “ma” with different tones yields completely different words: with a high level tone it means “mother,” with a rising tone it means “hemp,” with a low dipping tone it means “horse,” and with a high falling tone it means “to scold”. Mastering these tones is therefore crucial for effective communication in Chinese.

To help learners read the pronunciation of Chinese words without immediately having to learn the character symbols, the Hanyu Pinyin system was created, using the Latin alphabet with special marks to indicate tones. China adopted this system in 1958, and since then it has become the most widely used method of teaching Chinese internationally. Pinyin makes it easier to learn the correct pronunciation of Chinese syllables, and it is also extensively used for inputting Chinese text on computers and smartphones by typing the phonetics with Latin letters and having them automatically converted into Chinese characters.

Chinese Grammar Basics

In terms of grammar, Chinese is relatively simple compared to many other languages. For example, there are no verb conjugations at all; a verb stays in one form without changing for tense or person. Instead of different verb tenses, standalone words or particles are used to indicate time (for instance, adding the particle 了 to mark a completed action). Chinese also lacks grammatical case endings for nouns; there is no gender distinction in pronouns (the word tā means both “he” and “she”), and nouns do not have a special plural form (singular vs. plural is understood from context or by using numerals or quantifiers). Likewise, definite and indefinite articles (like “the” or “a/an”) are entirely absent in Chinese. A Chinese sentence generally follows a fixed structure of subject–verb–object, similar to English, with heavy reliance on word order to convey meaning. Instead of changing word endings to express grammatical relationships, Chinese uses prepositions and special particles (for example, adding 吗 at the end of a sentence to turn it into a question) to perform those functions.

Vocabulary and Word Formation

Chinese vocabulary consists mostly of monosyllabic units (each syllable forming a word or root meaning). Classical Old Chinese was largely monosyllabic in character, but in modern Chinese multi-syllable words have become much more common. This is partly due to the limited number of possible syllables in Mandarin: modern Chinese has only about 1,200 distinct syllables (including tones), compared to tens of thousands in English, which results in a large number of homophonous words (words that sound the same). For this reason, many concepts are expressed through compound words of two or more syllables to avoid ambiguity. For example, the word for “train” in Chinese is 火车 (huǒchē, literally “fire vehicle”), and “kitchen” is 厨房 (chúfáng, literally “cooking room”). Thus, word formation in Chinese is characterized by compounding, where multiple syllabic morphemes are combined to form a specific meaning, which helps differentiate meanings given the prevalence of similar-sounding syllables.

Historical Development of the Chinese Language

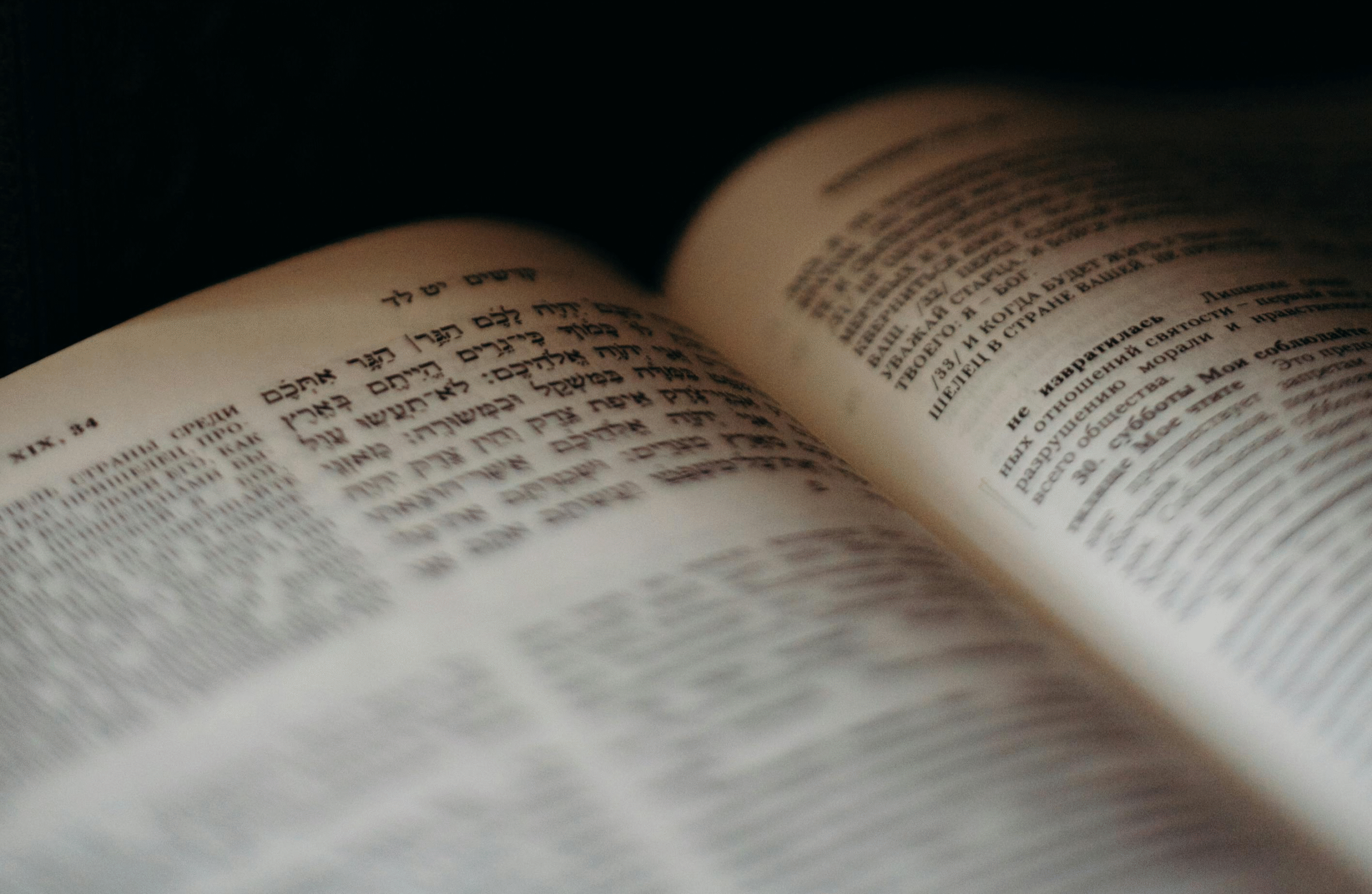

The Chinese language has undergone tremendous transformations over its long history. Classical Chinese (wényánwén, 文言文) remained the formal written language for many centuries (from around the 2nd century BCE onward), characterized by a terse style that was markedly different from everyday spoken language. This traditional literary language served as the unified medium of written communication among the educated across ancient China. However, at the start of the 20th century, a reform movement emerged calling for simplifying the language and making it closer to common speech. One of its pioneers was scholar Hu Shih, who in 1917 advocated adopting vernacular Chinese (báihuà, 白话) as the language of writing. Following the May Fourth Movement protests of 1919, the vernacular style gained broad momentum and was officially adopted as the national written standard in 1922. This shift from the classical to the colloquial style enabled Chinese to modernize and expand its expressive capacity to suit the modern era.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government launched an ambitious language reform program known as the language reform movement. This program had three main pillars: (1) simplifying the Chinese writing system by reducing the number of strokes in many characters to make them easier to learn and write; (2) adopting a unified national spoken standard, Modern Standard Chinese or Putonghua (普通话), based on the Beijing dialect, to serve as the common language throughout the country; and (3) creating an auxiliary phonetic alphabet in Latin letters – the Pinyin system mentioned earlier – to facilitate learning pronunciation and spreading the language. In 1956, Standard Mandarin was decreed to be taught in all schools in China, and a nationwide campaign began to promote its use. Official lists of simplified Chinese characters were also introduced (the first round in 1956 and a second in 1964) to reduce the complexity of many characters. These comprehensive reforms led to a notable rise in literacy rates in the ensuing decades, and succeeded in unifying China’s spoken and written language across its various regions.

Chinese in the Modern World

Today, the Chinese language is not confined to China alone; it is an official or widely spoken language in several Asian countries and among Chinese communities worldwide. There are large Chinese-speaking populations in East and Southeast Asia, such as Singapore (which has Chinese as one of its official languages), Taiwan (where Traditional Chinese is used), as well as in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and other countries. Chinese diaspora communities are also found across the Americas, Europe, and Australia, making Chinese a global cultural presence among overseas Chinese. Moreover, Chinese has been adopted as an official language in international forums; it is one of the six official languages of the United Nations, reflecting its importance among the world’s languages.

In recent decades, international interest in learning Chinese has grown in parallel with China’s rise as a global power. Statistics indicate that over 25 million foreigners are currently learning Chinese worldwide, and the cumulative number of foreign learners has reached around 200 million. The Chinese government plays an active role in promoting the language through establishing Confucius Institutes abroad; more than 1,500 Confucius Institutes and Classrooms have been set up in 159 countries, and over 13 million students have enrolled in their courses. Around 75 countries worldwide have incorporated Chinese into their school curricula as a foreign language. Standardized proficiency exams like the HSK (Chinese Proficiency Test for non-native speakers) have also become internationally recognized for assessing learners’ skills. Thanks to these efforts, and alongside the global spread of Chinese culture, Chinese has become one of the most important foreign languages pursued by millions in the 21st century.

The Chinese language combines a rich civilizational heritage with the demands of modern communication. From an educational standpoint, learning Chinese requires understanding its distinctive phonetic and tonal system and mastering its unique characters and tools; yet this challenge comes with the reward of engaging with one of the world’s oldest cultures. From a cultural and historical perspective, the evolution of Chinese shows how a language can serve as a unifying force for a vast people over millennia, and how today it continues as a language of global significance. As Chinese continues to spread and be learned internationally, it remains a bridge of understanding between China and the world, and a repository of a rich human heritage passed down through the generations.