The Chinese language is a global phenomenon with profound historical depth and increasing influence in the contemporary landscape. It is not merely a means of communication, but a reflection of rich culture, an economic engine, and a powerful diplomatic tool. This report aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the Chinese language, focusing on its unique linguistic features, historical evolution, growing role in global trade and diplomacy, the cognitive benefits its learning offers, and its deep cultural impact.

1. Introduction: The Significance of the Chinese Language in the Modern Era

The Chinese language family constitutes the most widely spoken linguistic group globally, boasting over 1.3 billion native speakers across more than 300 distinct languages. Within this vast linguistic diversity, Mandarin Chinese stands out as the most widely used native language worldwide, with approximately 1.12 billion native speakers, making it the second most spoken language overall after English.

Mandarin’s influence extends beyond its demographic dominance; it holds significant official status as an official language in mainland China, Taiwan, and Singapore. Its recognition extends to Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, and the United Nations, underscoring its international standing. Functionally, Mandarin serves as a lingua franca within the Sinosphere, facilitating communication and interactions among diverse Chinese speakers across various regions and dialects.

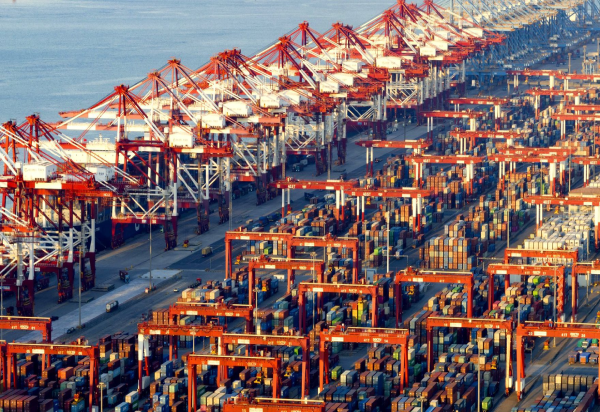

China’s immense economic expansion over recent decades has undeniably propelled Mandarin Chinese to unprecedented importance in global commerce. This rapid development has led to an inevitable and growing demand for Mandarin language education worldwide, as China has solidified its position as a pivotal hub for global investment, production, and trade. Proficiency in Mandarin is no longer just an advantage, but a valuable asset in international business and various professional pathways. It serves as a crucial key to unlocking opportunities for cross-border collaboration, diplomacy, and cultural exchange between China and other nations. The strategic importance of Mandarin Chinese continues to escalate in international business as China’s economic influence expands globally.

Research reveals an interesting tension between China’s immense linguistic diversity and the strong standardization imposed by Mandarin. While “Chinese languages” encompass over 300 distinct languages spoken by 1.3 billion native speakers , Mandarin emerges as the most widespread native language and the “lingua franca of the Sinosphere”. This dichotomy suggests that Mandarin’s unifying role is not merely a natural linguistic evolution, but a strategic political and cultural project. The existence of numerous mutually unintelligible dialects underscores the deeply rooted nature of regional identities, implying that while Mandarin serves as a bridge, a comprehensive understanding of Chinese society requires an appreciation of this underlying linguistic mosaic. This dynamic tension between diversity and unity is a defining characteristic of the Chinese linguistic landscape.

Furthermore, the research highlights the clear causal link between China’s rapid economic expansion and the rising importance of Mandarin. This demonstrates that linguistic capability, particularly in a language like Chinese, has transformed into a tangible economic and diplomatic asset. For businesses, it is a competitive advantage that enables direct market access and deeper engagement. For nations, it represents a form of “linguistic soft power,” where the promotion and adoption of one’s language can directly support broader geopolitical and economic objectives. This evolution underscores a significant shift in global power dynamics, where linguistic capital directly translates into leverage and opportunity.

2. History and Evolution of the Chinese Language and Its Major Dialects

The history of the spoken Chinese language spans approximately 4500 years, with the earliest direct historical linguistic evidence dating back to this period. The written form of Chinese first emerged in oracle bone inscriptions during the Late Shang period (c. 1250 – 1050 BCE), with the oldest examples dating to around 1200 BCE. Most experts agree that Sinitic languages share a common ancestor with Tibeto-Burman languages, forming the primary Sino-Tibetan language family.

From Proto-Sinitic to Modern Chinese

Old Chinese (before 500 BCE), also known as “Archaic Chinese,” is the ancestor of all current Chinese languages. Early evidence includes oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty and bronze inscriptions from the Zhou dynasty. Words were generally monosyllabic, and Old Chinese is believed to have been an uninflected language, possibly without tones. Evidence for its pronunciation comes from phonetic elements in characters and the pronunciation of borrowed Chinese characters in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese.

Middle Chinese (300-1100 CE) was prevalent during the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties. Its pronunciation is documented in rhyme dictionaries like Qieyun (601) and Guangyun (1008).

During the Early Modern Chinese period (1100-1900 CE), Mandarin, initially based on the Nanjing dialect, emerged as the dominant vernacular in northern China. This spread is partly attributed to the open plains of the north, which facilitated linguistic unification, in contrast to the mountainous and riverine terrain of southern China that fostered greater linguistic diversity. By the late 19th century, the Beijing dialect gradually replaced the Nanjing dialect in the imperial court.

The 20th century saw significant standardization efforts in the Modern Chinese period (1900-present). Standard Chinese (普通话 Pǔtōnghuà in mainland China and Singapore, or 国语 Guóyǔ in Taiwan) was formalized to promote national unity, with elementary school systems teaching it across mainland China and Taiwan. A major reform in March 1956 in the People’s Republic of China further solidified plans to introduce a simplified writing system to improve literacy.

Evolution of Chinese Characters

The earliest evidence of written symbols in China can be traced back over 8,000 years, with discoveries at the Jiahu site in Henan province dating to 6600 BCE. A unified writing system, known as

Oracle Bone Script (Jiǎgǔwén 甲骨文), developed approximately 3,000 years ago during the later stages of the ancient Shang Dynasty (c. 1250-1200 BCE).

This was followed by Bronze Inscriptions, which evolved from Oracle Bone Script. Characters became less pictorial and more symbolic, though they lacked uniformity, and distinct regional variations emerged.

Seal Script (Zhuànshū 篆书) developed from Bronze Inscriptions and became the unified and official script of the Qin Dynasty, characterized by more elongated characters.

During the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE), Clerical Script (Lìshū 隶书) became the dominant script, undergoing a profound modification towards symbolization, moving away from direct representation of physical objects. The modern shapes of Traditional Chinese characters largely appeared with Clerical Script around 200 BCE and stabilized around the 5th century CE.

Table 1: Major Chinese Character Evolution Stages

| Period/Dynasty | Script Name | Key Characteristics/Significance |

| Pre-6600 BCE | Jiahu Symbols | Earliest evidence of written symbols, found on pottery and turtle shells. |

| 1250-1200 BCE | Oracle Bone Script (Jiǎgǔwén) | First known unified writing system, divination inscriptions on animal bones and turtle shells. |

| Zhou Dynasty | Bronze Inscriptions | Evolved from Oracle Bone Script, characters became less pictorial and more symbolic, but lacked uniformity. |

| Qin Dynasty | Seal Script (Zhuànshū) | Became the unified and official script, characterized by more elongated characters. |

| Han Dynasty | Clerical Script (Lìshū) | Became the dominant script, profound shift towards symbolization, forming modern Traditional characters. |

| 5th Century CE – Mid-20th Century | Traditional Chinese Characters | Predominant standard form, stable since 5th century CE. |

| 1950s – Present | Simplified Chinese Characters | Government reform to increase literacy, based on pre-existing simplified forms, used in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia. |

The historical narrative demonstrates a recurring pattern of linguistic standardization efforts by Chinese dynasties and modern governments. However, in contrast, the geographical features of southern China, with its mountains and rivers, have “enabled greater linguistic diversity” , leading to the emergence of major dialect groups that are “largely not mutually intelligible”. This presents a clear paradox: despite centuries of top-down unification, significant linguistic fragmentation persists. This suggests that linguistic diversity in China is not merely a historical remnant, but a deeply ingrained aspect of regional cultural identities, often resisting centralized language policies. The continued existence of distinct, mutually unintelligible “dialects” (often classified by linguists as separate languages, as suggests) underscores the powerful influence of geography and local social structures on linguistic evolution.

Furthermore, the research highlights the exceptional continuity of the Chinese writing system, with the earliest evidence dating back over 8,000 years. Even the “simplified” characters introduced in the 20th century are often based on older, more efficient forms that had existed for centuries. This suggests that written Chinese is not merely a functional communication tool, but a deeply historical and living artifact. Its continuous evolution, despite shifts like simplification, has maintained a direct lineage that provides a unique cultural bridge to ancient texts, philosophies, and traditions. Thus, learning Chinese characters is not just an act of memorization, but an engagement with a profound historical and artistic lineage.

Overview of Major Dialect Groups

Chinese is not a monolithic entity; it comprises a family of languages whose speakers are largely mutually unintelligible. The major linguistic groups within Sinitic languages include: Mandarin, Jin, Wu, Huizhou, Gan, Xiang, Min, Hakka, Yue (Cantonese), and Pinghua, among others. The widespread prevalence of Mandarin throughout northern China is partly attributed to the region’s open plains, which facilitated linguistic unification. This contrasts sharply with the mountainous and riverine geography of southern China, which historically fostered greater linguistic diversity and the development of distinct dialect groups. Cantonese is a prominent dialect, spoken natively almost exclusively in Southeast China, particularly in Guangzhou and Guangdong province, as well as in Hong Kong, Macau, and among the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, Europe, and North America. It has approximately 75 million native speakers worldwide, positioning it among the top 20 largest languages globally, with more speakers than languages like Korean or Persian.

3. Distinct Linguistic Features of the Chinese Language

The Chinese language is characterized by several unique linguistic properties that set it apart from many other languages, presenting both challenges and opportunities for learners.

Tonal System

Mandarin Chinese is fundamentally a tonal language, meaning that the pitch or intonation used when pronouncing a syllable directly changes its lexical meaning. For instance, saying “tāng” with a high, level tone means “soup,” whereas “táng” with a rising tone means “sugar”. A common example of potential misunderstanding is the difference between “wǒ xiǎng wèn nǐ” (“I want to ask you”) and “wǒ xiǎng wěn nǐ” (“I want to kiss you”).

Mandarin employs four basic tones—a high-level tone, a rising tone, a low (dipping) tone, and a falling tone—in addition to a fifth neutral (toneless) tone. The Pinyin system, developed in the late 1950s, is the official romanization system used for learning Chinese tones, indicating them with diacritic marks above vowels. In contrast, Cantonese utilizes a more complex system of nine tones to differentiate pronunciation, including three “checked tones” used exclusively by syllables ending in a stop consonant or a glottal stop.

This indicates that the tonal system is not merely an addition to pronunciation, but an indispensable, fundamental component of lexical identity, especially given the language’s historical monosyllabic structure. In a language with a relatively limited phonetic inventory, tones serve as a crucial disambiguation mechanism, enabling a vast vocabulary to be built upon a smaller set of sounds. For learners, this means that mastering tones is not just a matter of “native” pronunciation but is fundamental to comprehension, underscoring the unique cognitive demands of acquiring a tonal language.

Writing System and Characters

Unlike alphabetic languages, Chinese is written using logographs, commonly known as characters. Each character is a distinct graphic unit that typically represents a word or morpheme, possessing a unique meaning and pronunciation. Many Chinese characters originated as pictographs, meaning their visual form carries an inherent meaning and story through their drawing and strokes, reflecting an artistic beauty.

Simplified vs. Traditional Characters: A significant divergence exists in the modern Chinese writing system. Simplified characters are predominantly used in mainland China, Malaysia, and Singapore, while Traditional characters remain prevalent in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. It’s important to note that many simplified characters were not entirely new inventions, but rather pre-existing, more streamlined forms. The simplification process involved reducing the number of characters and regularizing cursive forms into the standard script.

Unique Cantonese Characters: Due to distinct vocabulary, some Cantonese words do not have direct Mandarin equivalents, leading to the use of unique characters in Cantonese texts that a Mandarin speaker might not understand. Examples include 佢 (keoi5 – he/she/it), 嘅 (ge3 – possessive particle), and 喺 (hai2 – to be at).

Digraphia in Cantonese: Cantonese exhibits a state of digraphia, meaning it has two written standards. While standard written Cantonese largely adheres to written Mandarin for formal situations, a colloquial adaptation of spoken Cantonese is used for very informal contexts and for words unique to Cantonese.

Table 2: Mandarin vs. Cantonese: Key Linguistic Features Comparison

| Feature | Mandarin Description | Cantonese Description | Mutual Intelligibility |

| Tones | 5 tones (4 basic + 1 neutral) | 9 tones (including 3 checked tones) | Largely unintelligible |

| Initials | 23 initials | 19 initials | – |

| Finals | 35 finals | 58 finals | – |

| Romanization System | Pinyin | Jyutping | – |

| Character Usage | Primarily Simplified (mainland China, Singapore); Traditional in Taiwan | Primarily Traditional (Hong Kong, Macau); Simplified in mainland China | – |

| Unique Characters | No unique Mandarin characters not in Cantonese | Contains unique characters not in Mandarin | – |

| Adverb Order | Typically precedes the verb | Typically follows the verb | – |

| Double Objects | Indirect object precedes direct object | Direct object precedes indirect object | – |

Research indicates that Cantonese exists in a state of “digraphia,” where its speakers use written Mandarin for formal contexts while employing a colloquial adaptation with unique characters for informal situations. This dual written standard, coupled with significant spoken differences , points to a complex linguistic identity. This impacts deeper social, linguistic, and political dynamics. It suggests a hierarchical relationship where Standard Mandarin functions as the official and unifying written language, while Cantonese maintains its distinct spoken and informal written identity, particularly in regions like Hong Kong and Macau. This “digraphia” can create unique challenges for both native Cantonese speakers (who must navigate two written standards) and learners (who need to understand which written form is appropriate for different contexts).

Grammar

Standard Chinese grammar is notably straightforward, largely lacking inflection. This means words typically retain a single grammatical form, and categories such as number (singular or plural) and verb tense are generally not expressed through grammatical changes to the word itself.

Basic Word Order: The basic word order in Chinese is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO), similar to English. For example, “He hits someone” is structured as: 他 打 人 (tā dǎ rén), literally “He hit person”.

Topic-Prominent Language: Chinese is also considered a topic-prominent language. This means there is a strong preference for sentences to begin with the topic (given or old information) and end with the comment (new information). This structural preference allows for modifications to the basic SVO order, such as moving a direct or indirect object to the beginning of the clause for topicalization, or placing it before the verb for emphasis.

Pro-Drop Language: Chinese is a pro-drop, or null-subject, language, allowing the subject to be omitted when inferable from context.

Classifiers (Measure Words): Classifiers (量词; 量詞, liàng-cí) are mandatory when numerals (and sometimes other words like demonstratives) are used with nouns. Each countable noun is generally associated with a specific classifier to denote its counting unit (e.g., 一 瓶 酒 – yī píng jiǔ, “one bottle wine”). While many specific classifiers exist, the general classifier 个 (

gè) is colloquially acceptable for most nouns.

Adverbs and Adverbials: Adverbs and adverbial phrases typically appear before the verb but after the subject. In sentences with auxiliary verbs, the adverb usually precedes both the auxiliary and the main verb. Some adverbs of time and attitude can be moved to the beginning of the clause to modify the entire clause. Adverbs of manner can be formed from adjectives using the clitic

de (地).

Double Objects: In Mandarin, the indirect object typically precedes the direct object (e.g., 他 给我钱 – tā gěi wǒ qián, “He gives me money”). In Cantonese, the opposite is true, with the direct object coming before the indirect object (e.g., 他 給錢我 – keoi5 bei2 cin2 ngo5).

Plural Nouns and Pronouns: Chinese does not have inherent plural forms for nouns and pronouns. Plurality is indicated by adding specific characters, such as 们 (mén).

Comparative and Superlative Adjectives: Unlike English, Chinese does not have comparative or superlative forms for adjectives. Instead, additional characters are used to express these concepts.

Locative Phrases: These expressions can include a preposition (coverb), a postposition, both, or neither. A common spatial preposition is zài (在, “at, on, in”), which can also function as a verb.

Research suggests that Chinese grammar is “surprisingly straightforward” and lacks inflections, verb conjugations, and plural forms. This stands in stark contrast to the immense complexity posed by its tonal system and the vast number of logographic characters requiring individual memorization. This dichotomy points to an interesting linguistic balance. It can be interpreted as a form of linguistic compensation or trade-off. The relative simplicity of Chinese grammar might serve to alleviate the significant cognitive burden imposed by its complex phonological (tonal) and orthographic (character) systems. If Chinese were grammatically inflected like many Indo-European languages, the learning curve would be dramatically steeper, potentially hindering its widespread acquisition. This “streamlined” grammar allows learners to allocate more cognitive resources to mastering pronunciation and character recognition, suggesting a unique distribution of learning challenges and a different path to fluency compared to inflected languages.

4. Global Role and Economic Impact of the Chinese Language

The Chinese language, particularly Mandarin, is of increasing global significance in international trade, business, and diplomacy, with tangible economic benefits.

Mandarin as an Official and Lingua Franca

Mandarin Chinese holds official language status in mainland China, Taiwan, and Singapore, and is recognized in Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, and at the United Nations. It serves as the lingua franca of the Sinosphere, enabling communication among the vast majority of Chinese speakers, regardless of their native dialect. Beyond China, Mandarin is widely spoken in several Southeast Asian countries, including Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Brunei, the Philippines, and Mongolia, making it highly beneficial for those pursuing further study or business in these regions.

Importance in International Trade, Business, and Diplomacy

In today’s interconnected global economy, language is the foundation for successful international trade relationships. China, with its rapid economic expansion, has elevated Mandarin Chinese to unprecedented importance, making its mastery essential for businesses seeking to access the world’s second-largest economy and maintain a competitive edge. Companies that strategically invest in accurate and culturally informed Chinese translation and interpretation services are better positioned to capitalize on expanding opportunities. This investment also demonstrates crucial respect for Chinese business culture, which values precision and attention to detail.

Understanding Mandarin Chinese extends beyond mere linguistic capability; it signifies a commitment to building long-term relationships based on mutual respect and cultural understanding, particularly when navigating the concept of guanxi (relationship-building), a cornerstone of Chinese business etiquette that necessitates nuanced communication and cultural sensitivity. Language barriers pose significant risks, especially in contract negotiations where subtle linguistic nuances can drastically alter the interpretation of terms and conditions. Accurate translation of technical documentation is vital to ensure compliance with Chinese regulatory standards and operational requirements, thereby mitigating risks of litigation and operational failure. Professional translation and interpretation services foster trust, which in turn facilitates smoother negotiations, faster decision-making, and stronger long-term partnerships. This foundation of trust is paramount in Chinese business interactions. Confidence in navigating complex Chinese-speaking markets, including intricate regulatory environments and technical standards, significantly increases when supported by professionals who understand both the linguistic and regulatory landscapes.

Role of Confucius Institutes in Promoting Language and Culture

Confucius Institutes (CIs) are non-profit educational institutions jointly established by Chinese and foreign partner institutions. Their stated aim is to promote Chinese language and culture, support local Chinese language teaching internationally, and facilitate cultural exchanges. These institutes conduct Chinese language teaching and research, provide training for Chinese language teachers, develop learning resources, organize language and cultural exchange programs, and administer examinations and certifications related to Chinese language and culture. Confucius Institutes are described as a form of “public diplomacy,” through which China aims to use language and culture to enhance its image overseas and create a positive international environment. Their curriculum varies, with some branches focusing on business Chinese while others emphasize everyday language skills.

Economic Benefits of Chinese Language Proficiency

Proficiency in Mandarin can significantly boost an individual’s total income and wage income. It demonstrably improves job search efficiency by enabling employees to better understand their skills and match them to employer requirements. Many recruitment processes require Mandarin, facilitating faster and more effective communication and information transfer. Skilled Mandarin speakers can communicate more effectively with colleagues, leaders, and customers, thereby increasing work efficiency. Language proficiency expands social networks, increasing opportunities for individuals to gain more experience, knowledge, and skills. It also positively impacts consumption, reduces discrimination, lowers search costs, and enhances cultural and social activities. From an employer’s perspective, Chinese proficiency serves as an important screening criterion in the hiring process, even if it’s not always a direct prerequisite for salary increments. For certain sectors, such as tourism and service industries, Mandarin proficiency can be a prerequisite for employment.

Research clearly demonstrates a strong causal relationship between China’s economic growth and the global demand for Mandarin. Data indicates that “China’s rapid economic expansion has elevated Mandarin Chinese to unprecedented importance” and that this growth has “fueled an inevitable demand for Mandarin lessons”. Furthermore, the economic benefits for individuals are explicitly outlined: Mandarin proficiency “can significantly promote the total income and wage income” and “improve the efficiency of job search”. This suggests that the global rise of Mandarin is not merely a cultural or academic trend, but is fundamentally driven by economic utility. Individuals and businesses are increasingly incentivized to acquire Chinese language skills not just for cultural enrichment, but for tangible economic benefits and a competitive edge in the global marketplace.

Confucius Institutes are consistently presented as “public educational and cultural promotion programs” aimed at “promoting Chinese language and culture” and “facilitating cultural exchanges”. Crucially, they are explicitly described as a form of “public diplomacy” intended to “promote China’s image overseas and create a positive international environment for China”. This framing goes beyond simple language instruction. This reveals a deliberate and strategic deployment of language and culture as “soft power” tools by the Chinese state. By fostering linguistic and cultural understanding globally, China aims to build goodwill, enhance its international reputation, and indirectly advance its broader economic and diplomatic objectives. This approach suggests that cultural engagement is not a separate endeavor, but an integral part of China’s foreign policy, using the appeal of its language and rich heritage to cultivate long-term relationships and influence global perceptions, thereby shaping the international environment in its favor.

Research repeatedly emphasizes that Chinese business culture places significant importance on the concept of guanxi (relationship-building), which requires “nuanced communication that respects cultural sensitivities”. It further clarifies that “understanding Mandarin Chinese extends beyond linguistic capability” and “represents commitment to building long-term relationships based on mutual respect and cultural understanding”. This indicates that linguistic accuracy alone is insufficient for effective engagement. This points to a deeper requirement for successful interaction in Chinese-speaking contexts: cultural fluency. True mastery in business and diplomatic environments necessitates understanding the intricate social fabric of

guanxi, which is intrinsically linked to communication patterns like indirectness, the concept of “saving face” (Miànzi), and respect for social hierarchy. Therefore, language learning for these purposes must integrate robust cultural training. Without this nuanced cultural understanding, even perfect linguistic translation may fail to achieve desired outcomes, highlighting that language is a mirror of cultural values, and effective communication requires internalizing these values.

5. Cognitive Benefits of Learning Chinese

Learning Chinese, especially with its unique tonal and logographic features, offers significant cognitive advantages by stimulating brain growth in distinct ways.

Impact of Tonal Language on Auditory Processing and Music Perception

Learning a second language, particularly an intellectually challenging one like Chinese, offers fundamental benefits for cognitive development. Extensive experience with tonal languages, such as Chinese, has been shown to shape auditory processing in ways that generalize beyond the perception of linguistic pitch to the perception of pitch in other domains, notably music. Native speakers of tonal languages, on average, demonstrate an improved ability to discriminate musical melodies compared to speakers of non-tonal languages. Research suggests that tonal language experience enhances dimension-selective attention and improves subcortical encoding of pitch. For example, Mandarin speakers may exhibit an enhanced ability to direct attention to pitch when it is task-relevant. However, some studies also indicate that lexical tone experience might, in certain contexts, interfere with pitch perception in music or make it difficult to ignore pitch when it is not the primary focus.

Research clearly shows that learning a tonal language like Chinese provides significant cognitive advantages, particularly in areas related to auditory processing and music perception. However, some studies offer a nuanced perspective, suggesting that this specialized pitch processing might, in certain musical contexts, lead to interference or make it difficult to ignore pitch when it is not the primary focus. This presents a complex rather than uniformly positive picture. This implies that the cognitive adaptations required to master Chinese tones are highly specialized and can lead to both positive transfer effects (such as improved melody discrimination) and potential negative transfer effects or specific challenges in other auditory domains. This suggests that the brain re-tunes its auditory system to prioritize and intensely process pitch information, which, while beneficial for language comprehension, may come with subtle trade-offs in other areas of auditory perception.

Brain “Workout” and Improvements in Memorization, Attention Span, and Problem-Solving

The process of learning Chinese provides a rigorous “workout” for the brain, leading to measurable improvements in memorization abilities and attention span. As learners analyze and process new linguistic structures and identify effective techniques to master Chinese grammar and patterns, their brains automatically develop smarter and more efficient ways of expression. This challenging intellectual engagement is key to building confidence, fostering creativity, and enhancing multitasking abilities. Specifically, cognitive benefits extend to enhanced memory for logographs (Chinese characters) and increased awareness of tonal distinctions.

The snippets highlight that Chinese characters are logographs, fundamentally different from alphabetic systems, with each embodying unique meanings and pronunciations. This “complex writing system” is identified as a challenge, yet it is also noted that it “may also enhance their ability to memorize and recognize foreign words and characters”. This suggests a distinct cognitive interaction. This implies that learning Chinese characters activates and strengthens a different set of cognitive processes compared to acquiring alphabetic scripts. It likely enhances visual memory, pattern recognition, and the ability to link complex visual forms with abstract meanings. Thus, the brain’s “workout” is unique, cultivating skills in visual-spatial thinking and abstract symbol processing. These developed cognitive abilities can lead to broader advantages beyond language acquisition itself, such as improved non-linguistic visual processing or problem-solving skills that rely on pattern recognition.

6. The Deep Cultural Impact of the Chinese Language

The Chinese language profoundly and extensively influences culture, reflected in literature, philosophy, arts, and intricate social values that shape communication patterns.

Literature and Philosophy

Learning Chinese offers a gateway to a deeper understanding of one of the world’s oldest and richest continuous cultures, spanning over 5,000 years. In the 1st millennium CE, Chinese culture exerted significant dominance over East Asia. Classical Chinese was adopted as the language of scholarship and governance by ruling classes in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, leading to a massive influx of Chinese loanwords into their languages and the adaptation of the Chinese script itself. This linguistic and cultural influence persisted for centuries, until the 19th century in Korea and Japan, and the 20th century in Vietnam.

The Four Great Classical Novels: These literary masterpieces (Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, Water Margin, and Dream of the Red Chamber) are considered the most famous and important pre-modern Chinese fiction. Originating from the Ming and Qing dynasties, these novels have deeply permeated Chinese culture, inspiring countless tales, dramas, films, games, and performances across East Asia. These novels often depict characters embodying Buddhist, Taoist, and traditional Chinese moral philosophies.

The “Three Teachings” (Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism): These philosophies are traditionally considered a harmonious aggregate within Chinese culture, and have profoundly shaped Chinese thought and language.

Confucianism: This philosophy emphasizes respect, hierarchy, social harmony, and core values such as ren (humaneness), yi (righteousness), li (propriety/etiquette), zhong (loyalty), and xiao (filial piety). Historically, knowledge of Confucian writings was the primary criterion for entry into the imperial government. Its influence is evident in formal titles, the preference for indirect communication, and the crucial concept of “face” (

Miànzi) in Chinese interactions. Linguistically, its tenets are predominantly manifested at the lexical level through a rich array of honorifics, humble language, courteous speech, and euphemisms.

Taoism: In contrast, Taoism focuses on living in harmony with the Dao (Tao), often translated as “The Way” or “Principle”. It advocates for naturalness, spontaneity, simplicity, and

wu wei (non-action or effortless action). The term

Dao (道) itself is a central concept in Taoist philosophy and is deeply embedded in the language.

Buddhism: Upon its introduction, Buddhism significantly impacted various aspects of Chinese society, including art, statesmanship, writing, law, medicine, and physical sciences. The extensive translation of Indian Buddhist documents into Chinese profoundly influenced the semantics and syntax of medieval Chinese, enriching literary genres and rhetorical techniques, and increasing awareness of phonetics. This process introduced thousands of new words into the Chinese lexicon, and many existing Chinese words acquired new connotations.

Arts and Expression

Chinese civilization has profoundly influenced diverse art forms, including architecture, music, dance, poetry, martial arts, and calligraphy.

Calligraphy: The art of writing Chinese characters is highly valued across East Asia, combining visual art with the interpretation of literary meaning. It is considered one of the four most sought-after skills and hobbies of ancient Chinese literati. Chinese calligraphy is closely related to ink and wash painting, sharing similar tools and techniques, and emphasizing motion charged with dynamic life. Calligraphy extends beyond mere writing, focusing on cultivating one’s character (

renpin) and adhering to correct writing styles.

Music: Chinese music is often composed to reflect the tonal qualities of the Chinese language, characterized by the use of vibrato and glissando. While conflicts can arise between linguistic tones and musical melody, listeners are often able to decipher sung words by identifying and preserving contrasts between prominent features. Traditional Chinese music has also influenced Western musical compositions, initially as an “exotic sound” in the 18th and 19th centuries, and later through the integration of Chinese aesthetic ideas and poetry in the 20th century. Classical Chinese poetry forms, such as

shi and ci, were often set to music and adhered to strict requirements for length, tonal patterns, and rhymes.

Social Values and Communication Patterns

Chinese communication patterns are deeply influenced by Confucian values that emphasize respect, hierarchy, and harmony.

Miànzi (Face): The concept of Miànzi is fundamental in Chinese culture, referring to a person’s prestige, dignity, and reputation within their social circles. Losing face is highly undesirable and significantly impacts cautious communication, especially in business and public settings.

Indirect Communication: To preserve Miànzi and social harmony, indirect communication is often preferred over directness, especially in sensitive or emotional situations, or in professional and formal settings. Examples include using phrases like “I’ll think about it” as a polite refusal, deflecting compliments, or softening criticism to avoid causing embarrassment.

Guanxi (Relationship-Building): This concept of “connectedness” is highly emphasized in Chinese business culture and requires nuanced communication built on trust, respect, reciprocity, and shared experiences. For Chinese people, wealth is often measured by their social networks (

guanxi), which are considered vital business resources. The emphasis on

guanxi and maintaining face often leads to a reluctance to say “no” directly, as a direct refusal can be perceived as jeopardizing the relationship.

Social Hierarchy: The hierarchical nature of Chinese society is reflected in communication patterns. In Chinese (or “high-context”) culture, verbal communication is more accurately interpreted in the context of nonverbal communication, such as gestures, stance, and tone, as well as social hierarchy and other background information. Strong displays of emotion, especially negative feelings, are seen as disrupting balance. Thus, Chinese people tend to rely on indirect comments and the broader context to convey messages.

Conclusion

The Chinese language, with all its complexities and richness, presents a unique paradigm for the interplay of language, culture, and economy. This report demonstrates that Chinese is not merely a means of communication for an immense number of speakers, but a dynamic force shaping the global landscape. From its ancient roots and continuous evolution over millennia, to its unique tonal system and logographic character system, Chinese offers distinct cognitive challenges that enhance learners’ mental capacities.

The increasing role of Mandarin as an official and lingua franca across Asia and beyond solidifies its economic and diplomatic standing. Investing in Chinese language proficiency directly translates into business and professional opportunities, highlighting that language has become a strategic asset in today’s interconnected world. Confucius Institutes serve as a prime example of how language is utilized as a tool for public diplomacy, enhancing China’s image and global influence.

Furthermore, the Chinese language demonstrates an inseparable link with culture, where Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist values are manifested in literature, arts, and everyday communication patterns. Concepts such as Miànzi, guanxi, and indirect communication are not merely social rules, but are embedded in the language’s structure and are essential for effective and successful interaction in Chinese contexts. This underscores that a true understanding of the language extends beyond mere linguistic rules to encompass a deep assimilation of the cultural values that shape it.

In conclusion, the Chinese language is a multifaceted phenomenon worthy of study and appreciation. It is not only a window into a rich civilization, but also a key to the global economic and diplomatic future. As China continues to play a pivotal role on the world stage, the importance of its language will continue to grow, making its comprehension and mastery an invaluable investment in both human and cultural capital.