Continuity in Cuisine: Tradition Meets Innovation

While Chinese cuisine is celebrated for its ancient heritage and deep-rooted traditions, it is far from static. In the modern era, China’s culinary landscape is a dynamic realm where time-honored techniques and flavors seamlessly blend with contemporary trends, technological advancements, and growing global influence. This article explores the foundational building blocks of Chinese cooking, the diverse culinary experiences ranging from bustling street stalls to Michelin-starred establishments, and the remarkable global footprint of Chinese food, showcasing its ongoing evolution.

The Building Blocks: Common Ingredients and Essential Spices

The distinctive flavors of Chinese cuisine are built on a foundation of versatile ingredients and a carefully curated selection of essential spices, each contributing unique properties.

Common Ingredients and Their Uses

Soy Sauce: The cornerstone of Chinese seasoning, offering a salty umami flavor. Light soy sauce is thinner and saltier for seasoning, while dark soy sauce is thicker, less salty, and slightly sweet, used for coloring and depth.

Oyster Sauce: A thick, dark brown sauce with a salty, mildly sweet, and deep umami flavor, crucial for complex flavors and gloss in dishes like beef with broccoli.

Sesame Oil: A finishing oil with a strong nutty aroma, added at the end of cooking to enhance flavor in stir-fries, pickles, and sauces.

Shaoxing Wine: An amber-colored yellow rice wine that adds depth, tenderizes meats, and removes “gamey” odors.

Garlic and Ginger: Pungent and spicy, these are ubiquitous, balancing richness, adding bold flavor, and valued for their health benefits in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

Scallions (Green Onions): Used both as vegetables and aromatics, providing fresh, crisp flavor, often as a garnish or in flavor bases.

A relatively small list of core ingredients supports the immense variety of Chinese cuisine, pointing to incredible mastery of flavor combinations and transformations. The versatility and complementary nature of these staples allow for endless combinations and regional variations, enabling chefs to create distinctive dishes from a shared base. This efficiency also contributes to “cost differentiation” in Chinese manufacturing, reflecting culinary ingenuity where resourcefulness and deep ingredient knowledge lead to complex and diverse outcomes.

Essential Spices and Their Applications

Five-Spice Powder: A potent blend of star anise, cloves, Chinese cinnamon, Sichuan peppercorn, and fennel seeds, offering a unique balance of sweet, salty, bitter, and spicy flavors. Used for meat rubs, stews, and as a seasoning for fried foods.

Sichuan Peppercorn: Known for its numbing “mala” sensation, with a citrusy, slightly lemony flavor that cuts through rich foods.

Star Anise: A sweet, licorice-like aroma adds warmth to broths and braised meats; a key component in five-spice powder.

Chinese Cinnamon (Cassia Bark): Stronger and more intense than regular cinnamon, used for warmth in braised dishes.

Cloves: Earthy and bold, adding warmth and mild sweetness to soups and stews.

Ingredient/Spice Table

| Ingredient/Spice | Flavor Profile | Primary Culinary Uses | Traditional/Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soy Sauce | Salty, Umami | Marinades, seasoning, coloring, adding depth | – |

| Oyster Sauce | Salty, Mildly Sweet, Deep Umami | Meat dishes, noodles, adding gloss | – |

| Sesame Oil | Nutty, Aromatic | Finishing oil for stir-fries, pickles, sauces | – |

| Shaoxing Wine | Slightly Sweet, Aromatic | Meat marinade, odor removal, flavor enhancer | – |

| Garlic | Pungent, Spicy | Stir-fries, pickles, sauces, soups | Immunity boost, lowers blood pressure (TCM) |

| Ginger | Warm, Spicy | Seafood, stir-fries, soups, marinades | Anti-inflammatory, aids digestion (TCM) |

| Scallions | Fresh, Crisp, Pungent | Garnish, stir-fries, fillings, flavor bases | – |

| Five-Spice Powder | Sweet, Salty, Bitter, Spicy, Pungent | Meat rubs, stews, seasoning fried foods | Symbolizes balance and harmony in cooking |

| Sichuan Peppercorn | Numbing, Citrusy, Lemon-like | Mapo tofu, hot pots, stir-fries | Stimulates energy flow, aids digestion |

| Star Anise | Sweet, Licorice | Broths, braised meats, five-spice blend | Soothes digestion, brings good luck (festivals) |

| Chinese Cinnamon | Warm, Woody, Spicy | Red-braised pork, braised beef, stews | Warms body, improves circulation (TCM) |

| Cloves | Earthy, Bold, Mildly Sweet | Soups, stews, braised dishes, five-spice blend | Aids digestion, circulation, inflammation (TCM) |

In addition to flavor, spices like star anise and Chinese cinnamon are used in festive dishes for their “auspicious meaning” and traditional medicinal uses. Spices are thus not merely flavor enhancers but carry cultural symbolism and are embedded in the philosophy of “food as medicine.” Traditional beliefs about health and prosperity influence the choice and use of certain spices in cooking, adding another layer of cultural richness to Chinese cuisine, where spice selection reflects a fusion of taste, tradition, and well-being.

Mastering the Wok and Beyond: Core Chinese Cooking Techniques

The artistry of Chinese cooking is evident in its diverse techniques, many of which have gained global recognition for their efficiency, flavor preservation, and health benefits.

Stir-Frying (炒 chǎo): The most iconic and widely used method involves high heat in a wok with minimal oil. Ingredients cook quickly while preserving taste, texture, and color, making meats tender and vegetables crisp.

Steaming (蒸 zhēng): A healthy method using bamboo steamers over boiling water, efficiently cooking food without added oils or fats. Common for dumplings, vegetables, seafood, and chicken.

Deep-Frying (炸 zhà): Submerging food in hot oil to create a crispy texture. Ingredients are often coated with cornstarch for extra crunch.

Slow Cooking / Red Cooking (炖 dùn): A unique Chinese slow-cooking technique also called red cooking, resulting in richly colored dishes and tenderized tough meat cuts. Uses soy sauce, Chinese rice wine, rock sugar, and often five-spice powder.

Braising: Similar to slow cooking, braising softens large ingredients, simmering in a small amount of liquid over low heat for extended periods.

Techniques like stir-frying are known for their speed and minimal fuel use, while steaming emphasizes health. Slow cooking transforms tough meats into tender dishes. These methods were developed with a dual focus: maximizing flavor and texture while being resource-efficient and often health-conscious. Practical needs (e.g., fuel scarcity, desire for tender meat) and philosophical beliefs (e.g., health) drove the innovation and refinement of these methods. This explains why Chinese cooking is often seen as both flavorful and relatively healthy, and why these techniques have been widely adopted globally.

From Street Stalls to Michelin Stars: Culinary Experiences in Modern China

China’s contemporary food scene is a vibrant spectrum, ranging from the immediate sensory explosion of street food to the refined artistry of fine dining, all increasingly shaped by technological integration.

Vibrant Street Food Culture

Chinese street food is more than a meal; it’s a social and sensory experience of aromas, colors, and flavors that embody local histories and tastes. Dishes are quick, flavorful, and traditional, such as jianbing (savory crepes) and chuan’r (spicy grilled skewers). It’s considered “the great equalizer,” offering authentic flavors at low prices and fostering interaction between vendors and customers.

Street food is described as a “social experience” and a “great equalizer”, offering “unfiltered taste” and “authentic flavors”. This suggests it’s more than fast food—it enhances cultural immersion and social interaction, making it a vital part of daily life and an important informal economic sector. It also serves as a direct link to regional culinary traditions. For tourists, engaging in street food provides a more authentic and immediate cultural experience than formal dining, and its affordability makes it a staple of urban life.

Rise of Fine Dining

China’s dining scene has seen a remarkable transformation with the emergence of fine dining, elevating traditional dishes into refined culinary experiences. These establishments focus on precision craftsmanship, artistic presentation, seasonality, and innovative reinterpretations of classic recipes. Chefs like Alvin Leung (“the Demon Chef”) embody this trend with “X-Treme Chinese” cuisine, blending fusion and molecular gastronomy.

The rise of fine dining and innovators like Alvin Leung reflects a deliberate effort to elevate Chinese cuisine globally. This isn’t just organic growth—it’s strategic evolution. Driven by increasing affluence and exposure to global culinary trends, this movement enhances China’s soft power and broader cultural influence. Economic development and global integration empower culinary innovation and international recognition. This shows China’s confidence in its culinary heritage—not merely preserving it, but innovating and presenting it in globally competitive forms.

Authenticity and Adaptation

The concept of “authentic” Chinese food is nuanced. While home cooking often represents the truest, most traditional form, restaurant food may be adapted for broader appeal. For example, North American-style Chinese food often substitutes traditional ingredients (e.g., bok choy with broccoli), uses more MSG and cream, and favors frying, differing significantly from authentic cooking which emphasizes boiling, steaming, and roasting.

Distinguishing between home cooking, street food, restaurant food, and Western Chinese food highlights that authenticity is not fixed, but a spectrum influenced by local adaptation, ingredient availability, and consumer preferences. Migration, trade, and cultural exchange drive culinary adaptation, creating new localized versions of Chinese cuisine which, while different from the original, become “authentic” in their new context. This encourages an open-minded view of global cuisines, appreciating their evolution and recognizing that culinary traditions are ever-changing.

Navigating the Digital Culinary Landscape

Mobile payments (Alipay, WeChat Pay) are ubiquitous in China, making it a largely cashless society. Foreign visitors can now link international credit cards to these platforms, streamlining transactions for everything from transport to shopping. Food delivery apps like Meituan and Ele.me have transformed the dining experience, offering endless choices and convenience. AI and big data are integrated for personalized recommendations and optimized delivery routes.

The rapid adoption of mobile payments and food delivery apps illustrates China’s leadership in digital transformation. Allowing foreigners to link their cards is a direct policy response to tourism needs. China’s robust digital infrastructure and government support for fintech innovation have enabled this cashless revolution and the rise of food delivery. This reshapes daily eating habits and enhances foreign visitor accessibility, driving tourism growth. It underscores China’s unique status where advanced technology is deeply embedded in daily life, including culinary experiences, offering unmatched convenience but requiring adaptation from visitors.

A Global Phenomenon: The Worldwide Spread of Chinese Cuisine

Global Influence and Adaptation

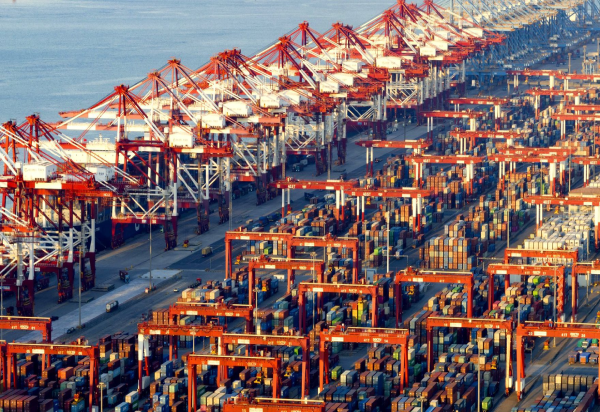

Thanks to the Chinese diaspora, historical trade routes like the Silk Road, and imperial expansion, essential Chinese foods (rice, soy sauce, noodles, tea) and utensils (chopsticks, the wok) have spread worldwide. Chinese cuisine has profoundly influenced other Asian cuisines (Cambodian, Filipino, Thai, Vietnamese) and sparked diverse global fusion foods, such as ramen (Chinese-Japanese fusion) and various sweet-and-sour dishes adapted to Western tastes.

The widespread diffusion of Chinese ingredients and techniques and the rise of fusion cuisines illustrate substantial cultural transmission. The Chinese diaspora and historical trade acted as “vectors” for culinary exchange, fostering global integration and adaptation of Chinese food. This, in turn, promotes cross-cultural understanding and strengthens China’s soft power. Chinese cuisine exemplifies how food transcends borders, fostering appreciation of diverse cultures and creating new culinary identities around the world.

Emerging Trend: Modern Plant-Based Foods

China is experiencing a surge in plant-based food innovations. In 2020, the Level 2.0 plant-based meat market (designed to mimic animal meat) was valued at $116 million, comprising over 70% of the Asia-Pacific market. Key consumer drivers include health benefits, food safety concerns (avoiding highly processed foods), and a desire for innovative products. Food tech innovations—such as AI and big data—are used to enhance sensory properties and assess traits at the molecular level.

The rise of plant-based foods in China, driven by health consciousness and environmental concerns, and enabled by food technology (AI, big data), signals a forward-looking culinary trend. This is propelled by evolving consumer preferences (health, food safety, sustainability) and technological advances in food science. Social shifts and tech progress are reshaping traditional eating habits, creating new food sectors. This positions China not only as a guardian of culinary tradition but also as a key innovator in the global food industry, addressing modern challenges and consumer demands.

Conclusion: A Culinary Legacy in Motion

Rooted in profound philosophy and rich history, Chinese cuisine continues to display remarkable dynamism. From ancient wisdom like yin and yang to the high-tech world of digital food delivery, from the subtle flavors of regional specialties to its widespread global adaptations, Chinese food is a living, evolving entity. It stands as a testament to China’s ability to honor its past while embracing innovation, making its culinary legacy one of the most influential and captivating in the world.