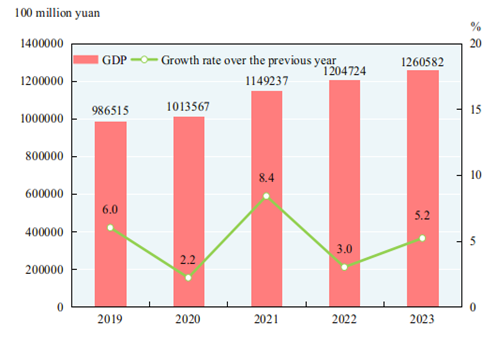

Internal trade in China has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past decades, encompassing the evolution of retail and wholesale systems, the rise of e-commerce, and continuous innovation in distribution channels. Once characterized by state-run stores and rationing in the planned economy era, China’s domestic commerce today is a dynamic, technology-driven landscape that plays a pivotal role in the national economy. The government’s recent “dual circulation” strategy underscores this importance by aiming to strengthen domestic demand as a complement to export-led growth.

Evolution of Retail and Wholesale Systems: Since the 1978 economic reforms, China’s retail sector has transitioned from strictly controlled state outlets to a competitive market with diverse players. In the 1980s and 1990s, private enterprises and foreign retailers entered the market, bringing modern retail formats to Chinese consumers. International chains such as Walmart and Carrefour opened hypermarkets in China, spurring local retailers to modernize and adopt best practices. Simultaneously, domestic retail brands expanded – for example, electronics retailers like Suning and GOME, and supermarket chains like Lianhua – benefiting from rising incomes and urbanization. On the wholesale side, China developed vast wholesale markets that distribute goods nationwide. The most notable is the Yiwu International Trade City in Zhejiang, renowned as the world’s largest small commodities wholesale market. Yiwu Market alone hosts tens of thousands of stalls selling hundreds of thousands of products, linking millions of producers and buyers domestically and globally. This expansion of retail outlets and wholesale hubs created an extensive distribution network across urban and rural areas, lowering logistics costs and improving the availability and variety of consumer goods throughout the country.

E-Commerce Boom and Distribution Innovation: In the past two decades, China has emerged as a global leader in e-commerce, fundamentally altering its internal trade. It is now the world’s largest e-commerce market, accounting for nearly 50% of global online transactions. In 2020, China’s online retail transactions reached about $2.29 trillion, with forecasts of $3.56 trillion by 2024. By 2021, China surpassed the US to become the largest e-commerce market with $1.5 trillion in revenue. Chinese tech giants dominate this arena: Alibaba Group (via Taobao and Tmall) holds roughly 50% market share, JD.com about 16%, and Pinduoduo around 13%, among others. Beyond online marketplaces, China pioneered “New Retail” – the integration of online and offline shopping. A prime example is Alibaba’s Hema (Freshippo) supermarkets, where customers use a mobile app to shop, pay digitally, and can opt for one-hour home delivery. These stores act as both retail outlets and fulfillment centers, blurring the line between physical and e-commerce. Additionally, novel channels like livestream commerce have exploded in popularity: live online sales events hosted by influencers (Key Opinion Leaders) have attracted an audience of over 388 million in China. Another innovation is the rise of “instant retail” services – platforms promising delivery of groceries and essentials within 30–60 minutes. Companies such as Alibaba, JD.com, and Meituan have collectively committed about 200 billion yuan ($28 billion) in subsidies to compete in this ultrafast retail segment. This fierce competition has drawn regulatory scrutiny over concerns of irrational pricing and deflationary pressure. Overall, the embrace of mobile technology (ubiquitous smartphone use and digital payments via Alipay, WeChat Pay, etc.) and logistics tech has made shopping in China highly convenient and efficient, seamlessly connecting producers, vendors, and consumers.

Government’s Role in Supporting Domestic Trade: The Chinese government has actively supported the development of internal commerce through policy and infrastructure. Following WTO accession in 2001, China further liberalized retail by allowing wholly foreign-owned retailers, which increased competition and quality. Domestic enterprises, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), have received tax breaks and financial support to spur entrepreneurship. In recent years, as external demand faced uncertainties, authorities placed greater emphasis on boosting domestic consumption. The government launched programs like consumer appliance trade-in subsidies to encourage households to upgrade to new, energy-efficient products, which significantly lifted sales of home appliances (some categories saw over 50% year-on-year growth). National shopping festivals (such as the Singles’ Day 11/11 and the mid-year “618” sale) are promoted to stimulate spending, with investments in postal and delivery infrastructure to handle billions of parcels during these events. In rural areas, the state has supported initiatives like the “Taobao Villages” program, training farmers and small vendors to sell agricultural and local products online, thereby integrating underserved regions into the modern market. Furthermore, the government’s investments in highways, high-speed rail, and 5G networks have enhanced connectivity, allowing goods from inland factories or farms to reach urban consumer markets rapidly. Regulatory oversight has also been strengthened to ensure fair competition – for instance, in 2021 Alibaba was fined for monopolistic practices, signaling to retail platforms that consumer interests and open markets must be preserved.

Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises: SMEs form the backbone of China’s domestic trade, dominating sectors from retail shops to supply-chain logistics. In sheer numbers, China had over 140 million registered SMEs as of 2020. Collectively, these firms contribute more than 60% of GDP, 50% of tax revenue, about 70% of technological innovation, and 79% of urban employment. This outsized role has led to numerous pro-SME measures. The government enacted the SME Promotion Law and periodically offers tax reductions and easier credit access for small businesses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many fees and taxes were temporarily waived for SMEs to help them survive the downturn. To boost innovation among smaller firms, the Ministry of Industry and IT introduced the “Little Giants” initiative in 2018, targeting high-potential small enterprises in strategic industries (like semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, etc.). By late 2024, China had recognized over 14,600 “Little Giant” firms (far exceeding the goal of 10,000 by 2025), granting them support in R&D funding, patenting, and market access. These SMEs often become key suppliers for larger domestic and multinational companies, plugging gaps in supply chains and driving localized innovation. Local governments have also set up business incubators and e-commerce training programs to help traditional family-owned shops and micro-enterprises go digital and reach broader markets.

Innovations in Distribution Channels: The efficiency of China’s internal trade is bolstered by cutting-edge logistics and distribution innovations. Companies have built vast smart logistics networks – for example, JD.com operates highly automated warehouses and uses AI for inventory management, and even deploys drones and driverless delivery robots for last-mile drop-offs in some rural areas. China’s express delivery services handle over 100 billion parcels annually, supported by a nationwide network of distribution centers; in 2023, express delivery volume reached 132 billion pieces with revenues around 1.2 trillion yuan. Wholesale and retail distributors are increasingly leveraging data analytics to optimize supply chains – linking point-of-sale data from stores directly to factories to implement just-in-time restocking. Another major trend has been community group buying platforms (pioneered by companies like Pinduoduo and Meituan) where residents of a neighborhood aggregate their grocery orders to get bulk discounts, with a coordinator in the community distributing the goods. While this model saw a boom during COVID-19 lockdowns, it continues to be part of the retail landscape in lower-tier cities. Furthermore, Chinese retailers are experimenting with unmanned smart stores, mobile vendors, and other novel formats to reach consumers everywhere. The competition among e-commerce giants has been particularly beneficial in pushing delivery times down – an expectation of same-day or next-day delivery is now standard in many Chinese cities. However, this “logistics race” has raised concerns about labor conditions for couriers and the financial sustainability of heavy subsidies, prompting regulators to call for “rational competition” in the sector.

Current Challenges in the Domestic Market: Despite its remarkable growth, China’s internal trade faces several challenges. One is market saturation in top-tier cities – consumers in metropolises like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen are spoiled for choice, meaning retailers must fight for market share and customer loyalty in a crowded field. Slowing income growth and high household savings can also temper consumption; Chinese consumers traditionally save a large portion of income, and economic uncertainties (such as a property market slowdown or global pandemic impacts) have at times made them cautious in spending. This has led the government to focus on boosting consumer confidence and reducing precautionary savings. Another challenge is the urban-rural divide – while e-commerce and delivery networks now reach rural villages, there is still a gap in consumption levels and access to services between coastal cities and interior rural areas. Bridging this gap by improving rural incomes and retail infrastructure remains an ongoing effort. Additionally, regulatory pressures are a double-edged sword: the government’s crackdowns on monopolistic behavior and data security (affecting big tech retail platforms) are beneficial for consumers and smaller competitors, but in the short term they forced industry giants to adjust their business models and slowed expansion plans. Rising costs are squeezing traditional retailers as well – labor wages have increased with development, and commercial rents in city centers are high, challenging the profitability of small brick-and-mortar shops. Finally, external factors can ripple into domestic trade. For instance, the US-China trade dispute and tech export restrictions have indirect effects on the economy, potentially influencing consumer sentiment. In response, China’s leadership has doubled down on cultivating the domestic market as a buffer against external shocks.

Looking ahead, the prospects for China’s internal trade remain robust. The sheer scale of the domestic market – total retail sales of consumer goods reached 47.15 trillion yuan in 2023 (about $6.8 trillion), a year-on-year increase of 7.2% – provides a strong foundation for growth. The continued urbanization of the population and the expansion of the middle class into smaller cities are expected to unlock new waves of consumer demand. Government policy will likely continue to encourage innovation and consumption, whether through digital yuan pilots to facilitate payments or further tax cuts on consumer goods. In sum, China’s internal trade has transformed into a sophisticated ecosystem of malls, markets, and mobile apps – a testament to decades of development – and it is poised to remain a key engine of China’s economic growth in the coming years.