In China, a Meal Is More Than Just Food

In China, a meal goes beyond mere sustenance; it reflects the social fabric and the pivotal role of the family. Eating is a vital part of daily life for the Chinese people, and meals are revered not just for enjoyment but for their role in achieving harmony and closeness among family members, strengthening social bonds.

Food in Chinese culture serves as a means of fostering relationships and expressing respect, playing a significant role in enhancing social cohesion. It symbolizes various aspects of life such as health, happiness, love, and wealth. This continuous emphasis on food as a vehicle for social interaction, familial hierarchy, and symbolic meaning elevates it beyond mere nourishment. It becomes a tool for communication, a ritual, and a repository of cultural values. Thus, understanding Chinese food culture requires looking beyond ingredients and techniques to grasp its profound social and philosophical dimensions. Eating becomes an enactment of cultural norms, a reinforcement of societal structures, and a channel for expressing complex emotions and aspirations.

2. Food as a Mirror of Culture: Traditions, Festivals, and Celebrations

Food plays a central role in strengthening familial and social bonds in China. It is a medium of social bonding, typically consumed communally, with shared dishes on a round table to foster interaction. In Chinese households, affection may be shown by placing choice food items in a loved one’s bowl, an act equivalent to expressing care and love. The family reunion dinner, especially during the Lunar New Year, is a cherished tradition, featuring dishes such as dumplings, fish, and spring rolls — each symbolizing prosperity, abundance, and wealth.

The deep-rooted symbolism in Chinese cuisine transforms food from mere sustenance into a complex system of expressing hopes, values, and social ties, enhancing cultural and social unity. For instance, dumplings represent wealth and prosperity, while fish (homophonous with “surplus”) is served at festive occasions to signify abundance. Long noodles symbolize longevity and are served on birthdays. These symbolic meanings are often derived from the food’s appearance, its name (homophony), or intrinsic qualities. This deep integration of symbolism means that every meal, especially during festivals, is a ritual act reinforcing cultural beliefs and collective aspirations. Chinese food culture is thus highly intentional and layered with meaning, making it a powerful vehicle for cultural transmission, ensuring that traditions, values, and wishes are passed down through generations.

Festive Dishes and Their Symbolic Meanings:

| Dish | Occasion | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Dumplings | Chinese New Year | Wealth and prosperity |

| Fish | Festive celebrations | Abundance and surplus |

| Long noodles | Birthdays | Longevity and a long life |

| Sweet rice cake | Gift for lovers | Strength of bond and love |

| Sweet dumplings | Lantern Festival | Love and unity |

| Pomegranate | Weddings | Fertility and love |

| Whole roasted pig | New Year, gatherings | Abundance, wealth, host’s generosity |

| Rice | Spring Festival | Fertility and abundance |

| Oranges and tangerines | Chinese New Year | Good luck and wealth (golden color, names) |

Food in Special Occasions:

Weddings: A tea ceremony is held where the bride and groom serve tea to elders, symbolizing respect and gratitude.

Funerals: Food and drink offerings are made to honor the deceased’s spirit.

Ancestor Worship: Dishes are presented to ancestors, rooted in filial piety, respect, and remembrance.

Food rituals during formal and family events reflect a strict social order based on respect and hierarchy. Seating arrangements, order of serving, and deference to elders all indicate that food is a stage for enacting social roles and affirming familial and societal hierarchies. This underscores that Chinese dining is not a casual affair but a highly ritualized social event. Food serves as a powerful medium of nonverbal communication, conveying respect, affection, and social status. It is a mechanism through which cultural norms are learned, performed, and maintained, highlighting the collective nature of Chinese society over individualism.

3. Philosophy of Chinese Food: Harmony and Balance

The Chinese relationship with food transcends sensory pleasure and reaches deep into philosophy, where harmony and balance are central to every aspect of food preparation and consumption.

Yin and Yang in Food

The yin-yang concept is fundamental to Chinese culture and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), representing opposing yet complementary forces. In dietary terms, foods possess properties that either cool or warm the body, nourish or stimulate, calm or energize.

Yin is associated with coolness, moisture, passivity, and darkness. Yin foods are typically cooling and moistening (e.g., most fruits, leafy vegetables, certain seafood like crab), recommended when there is excess yang (manifesting as heat, inflammation, or hyperactivity).

Yang is linked to warmth, dryness, activity, and light. Yang foods are warming and invigorating (e.g., red meat, root vegetables, warming spices like ginger and cinnamon), consumed to balance excess yin (manifesting as coldness, fatigue, or lethargy).

The goal is bodily harmony, where neither yin nor yang dominates. Seasonal foods are believed to provide the body with what it needs at that time, aligning with yin-yang principles.

These ancient philosophies are not just theoretical but are applied daily in cooking to achieve physical balance and cosmic harmony. Their integration into practical culinary choices reveals a worldview deeply rooted in holistic balance, energetic harmony, and preventive health, making each meal a therapeutic and philosophical act.

Five Elements Theory (Wu Xing) in Cooking

The Wu Xing (Five Elements) philosophy explains interactions and cycles in nature, serving as a framework for understanding the formation and connection of all things in the universe. The elements are:

Metal (strength), Wood (growth), Water (flow), Fire (energy), Earth (stability)

These interact through a cycle of generation (wood → fire → earth → metal → water) and regulation (metal restrains wood, wood restrains earth, etc.) to maintain balance. Each element corresponds to:

Five tastes: sour, bitter, sweet, pungent, salty

Five colors, seasons, and bodily organs

The Shandong cuisine exemplifies this harmony, combining the five flavors for balanced culinary experiences that reflect Confucian ideals of unity. This connection between philosophy and cooking shows how deep-seated philosophical principles permeate everyday culinary practices.

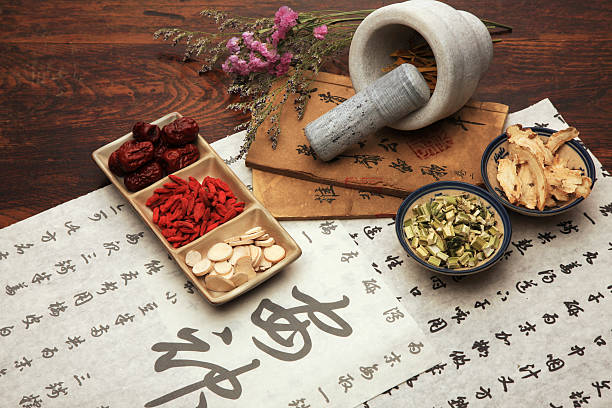

Food as Medicine in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

In TCM, food is medicine. It is believed that foods have healing properties that balance yin and yang and promote health. Diet therapy is the first line of treatment for illness, with healthy eating maintaining digestive health via the stomach and spleen.

TCM dietary practices aid emotional balance, detoxification, and purification. Ingredients like ginseng (boosts energy) and goji berries (vitality and longevity) are renowned for their therapeutic effects.

Integrating TCM into daily eating practices highlights a preventive approach to health, where food is the first defense against illness — a stark contrast to Western medicine’s post-disease treatment focus. This underscores a deep cultural belief in diet’s power to influence well-being and longevity, embedding culinary traditions into an evolved health system, making food essential to daily health, not merely a luxury.

4. Chinese Table Etiquette: Rules of Respect and Communication

Chinese table etiquette is a complex system of nonverbal cues reflecting respect, social hierarchy, and even superstitions, making dining a culturally rich experience.

Seating Hierarchy and Dish Presentation

In formal dining, seating order is critical. The seat facing the entrance is the seat of honor for the highest-ranking guest, who sits first, followed by others in descending order of status. The host takes a modest seat near the kitchen.

Elders are honored by being served first.

The best dishes are placed in front of the head of the family and distinguished guests.

Each rule — from seating to chopstick use — carries specific social or symbolic meaning, underscoring that dining is a performance where etiquette is vital to show respect and maintain social harmony. It reflects broader societal values of indirect communication, deference, and symbolism.

Chopstick Etiquette (Dos and Don’ts)

Chopsticks (Chinese fork) are standard dining tools. Etiquette includes:

Lay them evenly on the plate edge or chopstick rest.

Avoid sticking them upright in food, especially rice (resembles funeral rites).

Don’t cross them (×), rub them together, chew on them, or use them to rummage in shared dishes.

Use designated chopsticks for transferring food, not your personal pair.

Unique Customs

Customs that may seem “strange” to outsiders are expressions of appreciation and hospitality:

Burping is a sign of enjoying the meal and pleases the host.

Leaving some food shows the host provided abundantly.

Not flipping fish (especially in South China) avoids bad luck (“capsizing boats”); bones are removed instead.

Toothpicks may be used politely, with the other hand covering the mouth.

In some regions, a messy table signals a good meal. These customs, though impolite elsewhere, are positively interpreted in China, illustrating the need for cultural relativity in understanding etiquette.

5. Chinese Cuisine in the Modern Era: Challenges and Evolutions

Chinese cuisine is undergoing profound transformation in response to globalization, technological advancement, and contemporary challenges.

Globalization’s Impact

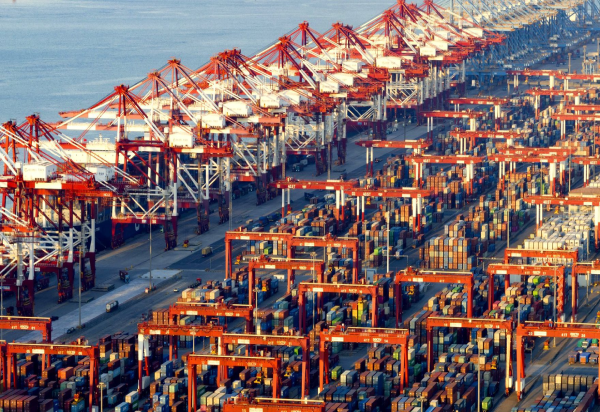

Chinese restaurants now number around 700,000 worldwide, worth ~3 trillion yuan in 180+ countries. Brands localize menus to suit foreign palates, creating tension between authenticity and adaptation. Popular dishes like sweet and sour pork, Kung Pao chicken, and fried rice have global appeal.

Contemporary chefs fuse regional traditions with global trends, creating fusion dishes blending Chinese with French, Japanese, or Nordic cuisines. Studies show that Chinese migrants and youth increasingly incorporate Western foods, indicating a dynamic tension between tradition and modernity.

Domestic Trends

Retail has shifted from small stores to supermarkets and online platforms, offering year-round fresh produce. The prepared foods sector has boomed, with pre-processed ingredients (washed, chopped) from central kitchens.

Modern diets favor healthy ingredients like tofu, fresh vegetables, and fish, with rising health awareness and reduced salt and fat.

Technology in Dining

Technology has revolutionized dining in China. Digital screens replace paper menus; orders and payments are done via apps like WeChat. Some restaurants use robots for serving, and menus often include photos and codes due to complex Chinese dishes.

This digitization and automation challenge traditional dining experiences, raising questions about preserving cultural essence amid modern efficiency.

Contemporary Challenges

China’s food system faces climate change (heat, drought, floods), industrialization, urbanization, and population growth, impacting crop yields and necessitating grain imports.

A rising middle class has led to dietary shifts — higher consumption linked to wealth. Reports warn of potential food crises (egg, milk, oil shortages) due to natural disasters, disease, and geopolitical tensions, driving prices up and triggering rationing and restaurant closures.

These pressures may spur innovation but threaten sustainability and regional culinary diversity.

6. Conclusion: The Future of Chinese Cuisine — Authenticity and Innovation

Chinese cuisine exemplifies how culinary traditions evolve while retaining cultural and philosophical essence. From ancient techniques and yin-yang philosophy to globalization and technology, it remains resilient and innovative.

Chinese food is in constant evolution, balancing authenticity with strategic innovation, ensuring its continuity as a global culinary force. Its adaptability — from ancient trade to modern tech — shows that change is integral to Chinese food culture.

Current trends (globalization, prepared foods, digital dining) are the latest in a long history of transformation, often driven by strategy (health focus, localization) rather than mere reaction.

Authenticity in Chinese cuisine is dynamic, continuously redefined through engagement with new influences and challenges. Its ability to integrate new elements while preserving core values guarantees ongoing appeal and global significance.

The future promises a rich dialogue between tradition and innovation, where ancient culinary wisdom is amplified by cutting-edge science and technology, ensuring Chinese cuisine remains dynamic and globally satisfying.