Introduction: Chinese as a Pivotal Language in the Interconnected 21st Century

In an increasingly interconnected world, the Chinese language has transcended its geographical boundaries to become a pivotal force in global affairs. Driven by China’s remarkable economic ascent and its growing role on the international stage, Mandarin Chinese, in particular, has emerged as an indispensable tool for trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. This article explores the multifaceted global influence of Chinese, delving into its demographic reach, its critical role in the world economy, and its impact on international relations. Furthermore, it examines the rewarding yet challenging journey of learning Chinese, highlighting both the linguistic hurdles and the profound personal and professional benefits awaiting those who embark on this path.

1. A Language of Global Reach: Demographics, Economy, and Diplomacy

The sheer number of Chinese speakers, coupled with China’s global prominence, has elevated the language to an unparalleled position in the 21st century.

1.1. Demographics: The Vast Number of Chinese Speakers Worldwide

Chinese stands as the most spoken group of languages globally, boasting over 1.3 billion native speakers across more than 300 distinct languages. Within this vast linguistic family, Mandarin Chinese holds the distinction of being the world’s most spoken native language, accounting for an impressive 1.12 billion native speakers. This places Mandarin as the second-most spoken language overall, trailing only English in total speakers. Proportionally, over 16% of the world’s population speaks a form of Chinese language natively.

While Mandarin dominates in sheer numbers, other Chinese languages also command significant speaker populations. Cantonese, for instance, is spoken by approximately 75 million people worldwide, a figure that positions it among the top 20 largest languages globally, surpassing languages like Korean or Persian in speaker count. Beyond mainland China, Mandarin’s influence extends across Southeast Asia, with significant speaker communities found in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Brunei, the Philippines, and Mongolia. These statistics collectively underscore the immense scale of the Chinese-speaking population, with Mandarin leading the way as a global linguistic giant. This demographic weight naturally translates into significant economic and diplomatic influence, making the language a crucial asset in international interactions.

1.2. The Economic Engine: Chinese in International Trade and Business

China’s rapid economic expansion has undeniably elevated Mandarin Chinese to unprecedented importance in global commerce. For businesses seeking to engage with the world’s second-largest economy, effective communication in Chinese has become not merely an advantage, but an essential requirement for market access and maintaining a competitive edge, particularly for enterprises in regions like the Gulf.

Understanding Mandarin extends far beyond mere linguistic capability; it embodies a profound commitment to cultivating long-term relationships founded on mutual respect and cultural understanding. This is especially true given the emphasis on

guanxi (关系), or relationship-building, in Chinese business culture, which necessitates nuanced communication that respects cultural sensitivities. Language barriers, if not properly addressed, can introduce significant risks, ranging from simple miscommunication to profound misinterpretations in critical areas such as contract negotiations and technical documentation. Subtle linguistic nuances can dramatically alter the interpretation of terms and conditions, or compromise compliance with regulatory standards. Consequently, professional translation and interpretation services are not just beneficial, but critical for mitigating these risks and ensuring precision in international transactions.

For individuals, proficiency in Mandarin can significantly boost personal income and wages, enhance job search efficiency, improve overall work productivity, and expand professional and social networks. Employers increasingly value Chinese proficiency as an important screening criterion in the hiring process, recognizing its utility in a globalized workforce. The phenomenal economic growth of China and its emergence as a global hub for investment, production, and trade are directly fueling an inevitable demand for Mandarin language education worldwide. This establishes a clear causal relationship where economic power directly translates into increased linguistic importance and demand for language learning, underscoring the practical necessity and perceived value of Chinese for global business and individual career prospects.

The emphasis on guanxi and indirect communication in Chinese business culture means that linguistic fluency alone is insufficient for success. True effectiveness requires a deep cultural understanding to navigate subtle communication styles, avoid causing someone to “lose face” (面子,

Miànzi), and build genuine trust. This highlights that language learning in this context is inherently cultural learning, as the language serves as a vehicle for cultural values, and success depends not just on speaking the words, but on understanding the cultural principles that shape how those words are used and interpreted.

1.3. Diplomacy and Cultural Exchange: Chinese on the Global Stage

Beyond its economic might, the Chinese language plays a significant role in international diplomacy and the exercise of soft power. Mandarin holds the key to maximizing the benefits derived from cross-border collaboration, diplomatic engagements, and cultural exchange between China and other nations. The global popularity of Chinese as a second language continues its upward trajectory, particularly within educational institutions and language study centers worldwide.

A key instrument in this global outreach is the network of Confucius Institutes (CIs). These public educational and cultural promotion programs, established by the Chinese state, aim to promote Chinese language and culture, support local Chinese language teaching internationally, and facilitate cultural exchanges. Confucius Institutes provide Chinese language teaching staff and resources, administer examinations, and offer certifications in Chinese language and culture. They also serve as vibrant cultural hubs, hosting a wide array of extracurricular activities such as Chinese New Year festivals, Mid-Autumn Festivals, tea ceremonies, art exhibitions, musical performances, film screenings, and guest lectures. These institutes are widely viewed as a form of “cultural diplomacy,” strategically deployed to enhance China’s image overseas and cultivate a positive international environment conducive to its foreign policy objectives. This demonstrates a deliberate strategy to leverage linguistic and cultural exchange to enhance a nation’s global image, build international goodwill, and create a more favorable environment for its foreign policy objectives.

2. The Cultural Resonance of Chinese: Language as a Cultural Lens

The Chinese language is not merely a means of communication; it is a profound repository of China’s rich cultural heritage, deeply intertwined with its philosophy, literature, and artistic expressions.

2.1. Echoes of Antiquity: Language Embedded in Philosophical Traditions

Chinese culture is profoundly rooted in a trinity of philosophical traditions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. These philosophies are not abstract concepts but living principles that permeate daily communication and social interaction, with the language itself reflecting these values.

Confucianism, a philosophy central to Chinese culture for thousands of years, emphasizes respect for authority, the importance of education, a strong work ethic, and the preservation of harmony. These values directly influence how Mandarin speakers communicate. For instance, communication often reflects respect for social roles and authority, seen in the use of formal titles such as “Wang Lǎoshī” (Teacher Wang). In many situations, especially professional or formal settings, indirect communication is preferred to avoid conflict or embarrassment. Phrases like “I’ll think about it” (我再考虑一下,

wǒ zài kǎolǜ yíxià) are often polite refusals. The core concept of preserving harmony (和谐,

héxié) means Mandarin speakers might downplay disagreements or offer neutral statements to avoid disrupting social balance. The fundamental concept of “face” (面子,

Miànzi) is about maintaining dignity and respect in social interactions. Losing face, or causing someone else to lose face, is highly undesirable, which is reflected in how Mandarin speakers often communicate cautiously, especially in business or public settings. This demonstrates how deep-seated philosophical principles are not just abstract ideas but actively shape the pragmatic use of language. Understanding these roots is crucial for effective cross-cultural communication, as it explains

why certain phrases or approaches are preferred.

Taoism, in contrast to Confucianism’s emphasis on social order, is a spiritual or philosophical belief that highlights living in harmony with the universe, naturalness, purity, spontaneity, kindness, frugality, and obedience. Its origins date back at least to the 4th century BC.

Chinese Buddhism has extensively shaped Chinese society across various domains, including art, statesmanship, writing, law, medicine, and the physical sciences. The translation of a vast collection of Indian Buddhist documents into Chinese and their integration with works created in China into published literature had far-reaching implications for the diffusion of Buddhism throughout China. Chinese Buddhism is also characterized by the intercommunication between Indian spirituality, Chinese mythology, and Taoism.

2.2. Literary Heritage and Artistic Expressions

The Chinese language has profoundly influenced East Asian culture, extending its reach into literature, philosophy, and various art forms. Classical Chinese was adopted by scholars and ruling classes in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan in the 1st millennium AD. This led to a massive influx of Chinese loanwords, collectively known as Sino-Xenic vocabulary (e.g., Sino-Japanese, Sino-Korean, Sino-Vietnamese), and the adaptation of the Chinese script itself (e.g., Kanji in Japan, Hanja in Korea, Chữ Nôm in Vietnam). This adoption of Classical Chinese as the language of government and research in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam for centuries allowed scholars across diverse linguistic backgrounds to communicate and share knowledge. This created a shared intellectual and cultural sphere in East Asia, analogous to the role of Latin in medieval Europe, demonstrating Chinese language’s historical role as a regional unifier.

The Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature are considered the most famous and important pre-modern Chinese fiction: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, Water Margin, and Dream of the Red Chamber. These novels are widely recognized by most Chinese, either directly or through their numerous adaptations into Chinese opera and other forms of mass culture. They represent the climax of China’s literary success in traditional books, inspiring countless tales, dramas, films, games, and performances across East Asia.

Mandarin is exceptionally rich in idiomatic expressions, known as chéngyǔ (成语), which are typically four characters long. These idioms carry deep cultural significance and often reference stories from ancient Chinese literature, history, or philosophy. Mastering these idioms provides a direct gateway to understanding China’s rich historical narratives, moral lessons, and philosophical underpinnings, making them miniature cultural time capsules embedded within the language.

Beyond literature, Chinese culture has a global impact through its diverse artistic expressions, including traditional art, architecture, music, dancing, poetry, martial arts like Kung Fu and Tai Chi, and the deeply ingrained tea culture. Qigong, a tradition of spiritual, physical, and healing methods, combines physical flexibility, breathing systems, and constant focus and meditation, serving as a method to purify and heal the heart and connect with one’s inner self.

3. Embarking on the Learning Journey: Challenges and Rewards

Learning Chinese is an endeavor that demands dedication but offers profound rewards, both linguistic and personal.

3.1. Navigating the Challenges of Chinese Acquisition

The unique features of Chinese, particularly its tonal nature and logographic script, present significant hurdles for learners accustomed to alphabetic, non-tonal languages.

Pronunciation and Tones: This is often the most fundamental challenge for foreign learners, especially those from non-tonal language backgrounds. Mandarin’s four basic tones and a neutral tone mean that a slight variation in pitch can completely change a word’s meaning. Mispronouncing tones or, crucially, Chinese names, can lead to miscommunication and may even be perceived as a lack of respect or effort, given the cultural significance of names.

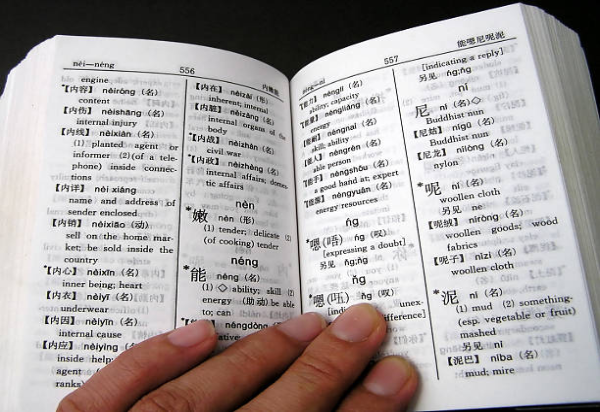

Characters and Words: Chinese utilizes a logographic writing system, where each character represents a word or concept, differing significantly from alphabetic systems. The task of learning the “vast array of characters” can be overwhelming. A significant cognitive burden arises from the inconsistency of sound-meaning association in many phono-semantic compound characters; only about 26.3% of these characters have phonetic components that accurately reflect their pronunciation. This means learners cannot reliably infer pronunciation from character components, making character acquisition a distinct and often more demanding task than vocabulary learning in alphabetic languages.

Grammar: While Chinese grammar is often described as simplified due to its lack of inflection (no verb conjugation, no plural nouns, no comparative adjectives) , it follows different rules and patterns that can initially seem daunting to new learners. The reliance on precise word order, particles, and context to convey meaning, particularly the concept of topic-prominence, introduces a different kind of complexity that requires learners to shift their grammatical intuition.

Listening Skills: For many learners, developing strong listening comprehension in Chinese is a formidable challenge, as it requires immediate processing of information, including subtle tonal distinctions.

Pedagogical Dilemma: While early exposure to Pinyin (the Romanization system) can aid phonetic discrimination and make initial learning less intimidating , over-reliance on Pinyin can potentially “delay the development of essential Chinese reading and writing skills” and “decrease students’ natural interest and learning motivation” for characters. This highlights a pedagogical tension where a beneficial tool can become a hindrance if not balanced with direct character learning.

3.2. Unlocking the Benefits: Cognitive, Career, and Cultural Advantages

Despite the challenges, the rewards of learning Chinese are profound, extending far beyond mere communication to encompass significant cognitive enhancements, substantial career advantages, and a profound cultural immersion.

| Benefit Category | Description |

| Cultural Enrichment | Gain a deeper understanding of one of the world’s oldest and richest continuous cultures. Appreciate the artistic beauty and stories embedded within each Chinese character, which are pictographic and carry unique meanings. |

| Cognitive Advantages | Provides an intellectual “workout” for the brain, improving memorization abilities, attention span, confidence, creativity, and multi-tasking skills. The experience of learning a tonal language like Chinese demonstrably shapes auditory processing, enhancing the ability to discriminate musical melodies and improving dimension-selective attention to pitch. This suggests the brain adapts to process subtle auditory cues more effectively, offering a unique cognitive advantage. |

| Career Opportunities | Significantly boosts career prospects, making one an attractive candidate in the recruitment market due to demonstrated multi-tasking, problem-solving, and discipline. Essential for expanding businesses into Chinese markets, understanding consumer psychology, and building crucial trust. Opportunities also arise as a Chinese tutor or a foreign language teacher in China. |

| Enhanced Travel Experiences | Allows for deeper, more authentic exploration of China, enabling hassle-free adventures in areas where English may not be widely spoken. Facilitates understanding of local history and customs. |

| Other Benefits | Widely spoken in other Asian countries (Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Brunei, Philippines, Mongolia). Provides an advantage in college applications and opens up more major choices. Enables enjoyment of Chinese movies, TV, and music in their original forms. Allows for a more authentic appreciation of Chinese cuisine. |

3.3. The Immersion Imperative: Why Cultural Immersion is Crucial

While structured language learning is undoubtedly important, true fluency and cultural competence in Chinese are best achieved through immersion. Chinese language immersion programs offer a deep dive into Mandarin, enabling students to rapidly improve their language skills through direct engagement and authentic cultural experiences. Immersion enhances both linguistic proficiency and a nuanced understanding of Chinese culture by integrating students into daily activities, celebrations, and routines that reflect the traditions and values of Chinese society.

Engaging directly with local culture and consistently using Mandarin in varying real-world contexts leads to significant and accelerated improvements in language skills. Research consistently indicates that students who study abroad in immersion programs demonstrate greater improvement in language skills compared to those studying in their home country, attributing this accelerated learning to continuous practice and exposure to the language in its natural environment. Cultural immersion serves as a cornerstone for achieving fluency in Chinese, as it directly links linguistic acquisition with cultural understanding. By participating in daily life and cultural events, learners gain practical language skills in context while simultaneously internalizing the unspoken cultural norms, etiquette, and values (such as

Miànzi and guanxi) that are essential for truly effective communication. This synergistic relationship means language skills are enhanced because of cultural engagement, and cultural understanding is deepened through language use in authentic settings, leading to holistic fluency.

Conclusion: The Transformative Power and Profound Rewards of Learning Chinese

The Chinese language, with its vast demographic reach, indispensable economic role, and profound cultural resonance, stands as a cornerstone of the modern global landscape. Learning Chinese is a transformative journey that extends far beyond acquiring a new skill; it is an invitation to engage with one of the world’s richest civilizations, to unlock unique cognitive potentials, and to open doors to unparalleled career and cultural opportunities. Despite its inherent challenges, the rewards of mastering Chinese are profound, offering a deeper understanding of the world and a unique perspective on human communication and culture.