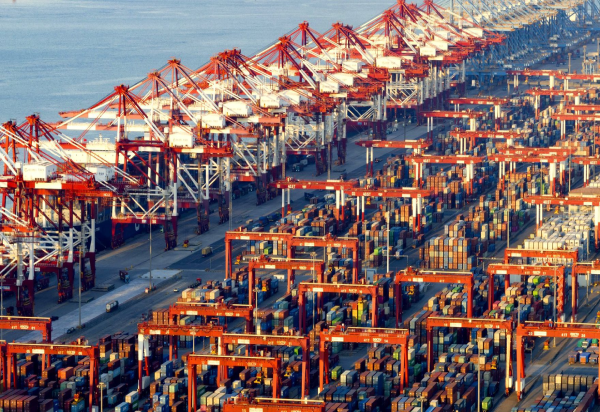

China’s foreign trade has expanded at a remarkable pace, transforming the country into a global trade powerhouse. China is currently the world’s largest exporter and the second-largest importer of goods. Its trade portfolio encompasses a broad range of partners and export industries, underpinned by active participation in multilateral trade agreements (such as the WTO and RCEP) and strategic initiatives like the Belt and Road. At the same time, China’s growing clout in global trade has led to friction with some countries, resulting in trade disputes and negotiations to rebalance trade relations.

Major Trade Partners: China’s top trading partners have evolved as its trade volumes surged. As of 2024, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has become China’s largest overall trading partner, with total merchandise trade close to $982 billion, followed by the European Union ($786 billion) and the United States ($688 billion). Other significant partners include South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, Russia, Australia, and India, among others. This diversity reflects China’s deep integration with both developed and developing economies. Trade with its Asian neighbors has grown especially fast – ASEAN overtook the EU and US in recent years, boosted by regional supply chain integration and the effect of the RCEP free trade agreement. Traditional markets like the US and EU remain crucial for China’s exports (despite recent tensions), accounting for large shares of high-value shipments. It’s noteworthy that trade with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries now makes up almost 46.6% of China’s total trade. In 2023, China’s goods trade with BRI-participating nations reached 19.47 trillion yuan (~$2.74 trillion), up 2.8% year-on-year. This indicates China’s growing commerce with emerging markets across Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, partly facilitated by infrastructure projects and investment under the BRI. For instance, Chinese trade with Latin America and Africa rose by 6–7% in 2023 as China increased imports of commodities (energy, minerals, agricultural goods) and exported more machinery and consumer products to those regions.

Exports and Imports: China’s export basket is dominated by manufactured goods, especially electronics and machinery. Its top export categories include telecommunications equipment like mobile phones (about 7.6% of exports), computers and other data processing machines (4.4%), electronic circuits and components (4.0%), along with automobiles (2.3%), and electrical items such as batteries and semiconductors (1.8%). This highlights China’s role as the global manufacturing hub for high-volume tech and consumer products. In recent years, exports of higher-value products – for example, electric vehicles, solar panels, and industrial robots – have surged, reflecting China’s move up the value chain. In 2024, exports of high-tech products like EVs, robotics, and 3D printers jumped over 40%, contributing to an overall 7.1% growth in exports (to 25.45 trillion yuan). On the other side, China’s imports are largely raw materials and intermediate goods needed to fuel its economy. The country is the world’s largest importer of integrated circuits (chips), which account for about 13.7% of its import bill, due to the enormous demand from its electronics assembly industry. China also imports vast quantities of crude oil (~13.2% of imports) to meet its energy needs, as well as iron ore (5.3%) for steel production, along with other commodities like copper, coal, natural gas, and agricultural products. This import profile underscores China’s reliance on foreign suppliers for critical inputs – from Middle Eastern oil to Australian iron ore and Southeast Asian foodstuffs – to sustain its industrial output. Over decades, China’s trade balance has consistently been in surplus; in 2023, its overall trade surplus (goods and services) was roughly 2.2% of GDP, although this can fluctuate with global demand and commodity prices.

Trade Policies and Agreements: China’s approach to trade policy combines multilateral engagement with selective bilateral and regional deals. After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China significantly reduced tariffs and opened various sectors, which propelled its export boom and integrated it deeply into global supply chains. At the same time, China employed industrial policies to develop strategic industries (like subsidies or state support for technology sectors), which have sometimes led to trade frictions with partners who argue these create unfair advantages. To cement its trade relationships, China has increasingly turned to free trade agreements. In November 2020, along with 14 other Asia-Pacific countries, China signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which came into effect in 2022. RCEP creates the world’s largest free trade zone, covering about 30% of global GDP. It brings together ASEAN members and key partners (China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand) into a unified framework that reduces tariffs (generally over a 20-year period) and harmonizes various trade rules. RCEP is expected to simplify supply chain logistics in East Asia and boost intra-regional trade. China is also pursuing other agreements: it has expressed interest in joining the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership) and has active bilateral free trade agreements with countries such as Australia (since 2015), South Korea (2015), Switzerland, Chile, and several others. These agreements help secure markets for Chinese exports and sources for imports, reducing reliance on any single partner. Additionally, China uses forums like the G-20, APEC, and BRICS to advocate for trade facilitation and investment flows. Domestically, the government has established pilot Free Trade Zones in various provinces to experiment with liberalization measures (e.g., easier customs procedures, looser capital controls) in support of trade.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): A cornerstone of China’s external economic strategy is the Belt and Road Initiative, launched by President Xi Jinping in 2013. This global infrastructure and connectivity drive aims to enhance trade links between China and over 140 participating countries across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America. The “Belt” refers to overland corridors (like railways and highways through Central Asia to Europe) and the “Road” refers to a maritime route connecting Chinese ports with Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean. In the decade since its inception, cumulative Chinese engagement (loans and investments) in BRI projects has exceeded $1 trillion. By improving infrastructure – building rail lines, highways, bridges, ports, and power plants – BRI projects aim to lower transportation costs and bolster trade between China and partner countries. For example, freight trains now regularly run from Chinese cities like Chongqing, Wuhan, and Xi’an to European hubs such as Duisburg and Madrid, cutting delivery times compared to sea freight. Such China-Europe Railway Express trains carried over 1.6 million TEUs (containers) in 2022 along dozens of routes. The BRI has significantly increased China’s trade with participating countries by creating new logistical networks. It also secures China’s access to vital commodities (energy from Central Asia and the Middle East, minerals from Africa) by diversifying supply routes. However, the initiative has faced challenges including debt sustainability concerns in some recipient countries and geopolitical pushback. Despite these issues, China credits the BRI for driving increases in trade – as of 2023, nearly half of China’s foreign trade was with BRI countries. If fully realized, studies project the BRI could boost trade among participants by 4–5% and add substantial momentum to global GDP by 2040.

Trade Frictions and Disputes: China’s growing trade dominance has not been without conflict. The most prominent clash has been the U.S.-China trade war that began in 2018. Citing unfair trade practices, the U.S. imposed steep tariffs on approximately $370 billion worth of Chinese goods. China retaliated with its own tariffs on tens of billions of dollars of U.S. exports. These tit-for-tat measures marked the largest trade confrontation in recent history. A partial “Phase One” agreement in January 2020 saw China pledge to buy more U.S. products (especially farm goods and energy) in exchange for tariff relief, but many U.S. tariffs remain in place, and China fell short of the purchase targets. The dispute has since evolved beyond tariffs: the U.S. has implemented export controls to deny China access to advanced semiconductors and chipmaking equipment, and is scrutinizing Chinese technology companies abroad (e.g., banning TikTok on government devices). China, in turn, has restricted exports of certain critical minerals (like rare earth elements) and passed new laws to protect its firms’ data and supply chains. Trade tensions have not been limited to the U.S. One high-profile example was China’s trade spat with Australia. In 2020, after Australia called for an inquiry into COVID-19’s origins, China imposed heavy tariffs and unofficial bans on Australian barley, wine, beef, and coal, effectively cutting off those exports. By 2023, diplomatic relations improved and China removed the 80.5% tariff on Australian barley and lifted its 218% anti-dumping duties on Australian wine, ending the three-year freeze on those imports. Elsewhere, the European Union has raised concerns about a flood of inexpensive Chinese goods. In September 2023, the EU launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicle (EV) exports, worried that state-subsidized Chinese EVs were undercutting European manufacturers. This could potentially lead to new EU tariffs on Chinese cars. India, too, has had economic friction with China: following a border clash in 2020, India banned around 300 Chinese mobile apps and tightened investment screening for Chinese firms, and bilateral trade growth has slowed. Despite these disputes, it’s notable that pragmatism often prevails – China and its partners have incentives to negotiate solutions, given China’s integral role in global supply chains and as a key market. For instance, even after rounds of tariffs, the U.S. remains one of China’s largest export markets (and China is a top market for U.S. agricultural products).

Looking forward, China’s foreign trade strategy seems to be shifting from an emphasis on sheer volume to higher-quality trade. Policies like “Made in China 2025” aim to reduce dependence on foreign technology and promote exports of higher-end goods, which is already evident in the growing tech content of China’s exports. At the same time, China is cultivating new trade corridors (as with BRI and RCEP) to lessen exposure to any single region. Trade with emerging economies is likely to deepen, as China provides an ever-growing market for commodities and consumer goods from those countries in exchange for supplying them with affordable machinery, infrastructure, and electronics. We may also see services trade become a larger part of China’s trade mix; currently China runs a deficit in services (importing more tourism, education, and financial services than it exports), but initiatives are underway to promote sectors like tourism, banking, and telecommunications abroad. Of course, external challenges remain – from geopolitical rivalries to potential protectionism – but China’s established status in global trade is firmly entrenched. Barring major disruptions, China is poised to continue shaping global trade patterns, leveraging its massive production base and domestic market, while adapting to the new rules and norms of international commerce in the 21st century.