This article presents a comprehensive analysis of China’s economic journey, from the transformative “Reform and Opening-up” period to the current phase of the “New Normal.” It explores the evolving drivers of growth, major structural challenges, and China’s growing global economic impact, including the Belt and Road Initiative. The report concludes with a forward-looking perspective on China’s economic trajectory and policy responses aimed at achieving sustainable, high-quality development.

Introduction: The “Chinese Economic Miracle” in Context

China’s economic transformation since the late 20th century represents one of the most remarkable growth stories in modern history. From a centrally planned economy plagued by poverty, stagnation, and relative isolation before 1979, China has emerged as the world’s second-largest economy by nominal GDP, and the largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) since 2016. This “Chinese economic miracle” has seen per capita GDP rise nearly 50-fold since 1978, lifting an estimated 800 million people out of poverty. China’s share of global GDP has grown from 4% in 2000 to 16% by 2018.

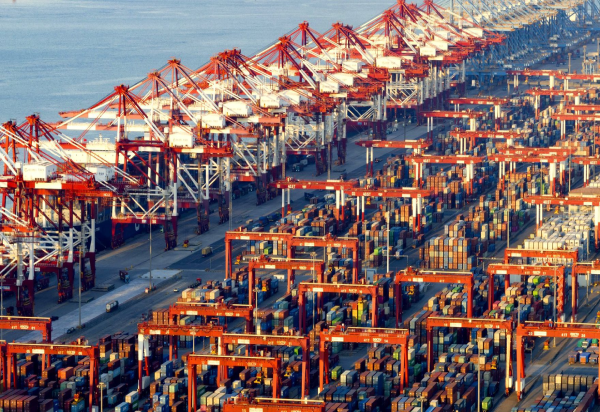

The sheer scale and speed of China’s economic rise have fundamentally reshaped the global economic landscape, shifting power away from the traditional G8 nations. China’s emergence as the world’s largest manufacturer and a pivotal hub in global supply chains underscores its indispensable role. However, the state-led nature of its economy and ongoing trade tensions add complexity and friction to its international economic relations, making China both an essential and challenging partner.

From “Reform and Opening-up” to the “New Normal”: A Historical Perspective

The roots of China’s economic dynamism lie in the “Reform and Opening-up” policies initiated by Deng Xiaoping on December 18, 1978. These reforms, termed “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” involved a two-phase transition toward a market-oriented economy. The first phase (late 1970s to early 1980s) focused on decollectivizing agriculture, which significantly boosted output by 8.2% annually (compared to 2.7% pre-reform), lowered food prices, and increased farmers’ incomes. This success freed labor for industrialization. Simultaneously, China opened up to foreign investment and allowed entrepreneurship.

The industrial sector saw substantial productivity gains through the dual-track pricing system and increased managerial autonomy. The share of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in industrial output dropped from 81% in 1980 to 15% in 2005, marking a deep shift toward market mechanisms and the private sector. Foreign capital played a crucial role in early industrialization. Although economic reforms paused briefly following political events in 1989, they resumed after Deng’s Southern Tour in 1992.

The “Reform and Opening-up” strategy was pragmatic and adaptive, prioritizing economic growth over political liberalization and demonstrating the Chinese Communist Party’s strategic flexibility in ensuring long-term stability and development. The timeline, with political reform halted in 1989 and economic reform resumed in 1992, clearly indicates the CCP’s willingness to adapt to internal and external challenges by focusing on economic outcomes. The steep decline in the SOEs’ industrial output share, from 81% to 15%, quantitatively reflects a profound structural shift toward market mechanisms, signaling a fundamental transformation in the economic model despite continued state guidance.

As the economy matured, real GDP growth naturally slowed from its peak of 14.2% in 2007 to 6.6% in 2018, with projections of 5.5% by 2024. The Chinese government recognized this as the “New Normal,” signaling a deliberate shift from an investment- and export-driven model to one increasingly reliant on private consumption, services, and innovation. This strategic shift is essential for avoiding the “middle-income trap.”

The transition to the “New Normal” reflects proactive recognition by policymakers of diminishing returns from traditional growth models and a strategic effort to rebalance the economy toward higher-quality, more sustainable growth engines. This acknowledgment of slowdown is not passive acceptance but part of a long-term economic plan. The stated need to shift toward consumption, services, and innovation, along with the explicit goal of avoiding the “middle-income trap,” illustrates a nuanced approach to long-term economic planning for continued development.

Current Drivers of Economic Growth

In the first half of 2025, final consumer spending emerged as a key driver, contributing 52% to China’s economic growth. This is supported by the booming “new consumption” trend, spanning entertainment (e.g., record-breaking box office earnings from Ne Zha 2, and games like Labubu) and lifestyle sectors (e.g., the “ice and snow” economy and rural tourism boom). Emerging consumption trends also include health-related spending, the rise of domestic brands, and increased demand from aging consumers, as the “silver economy” shows notable growth. Emotional consumption and the rapid expansion of instant retail further fuel consumer market growth.

In addition to consumption, emerging industries are gaining significant momentum, shifting economic growth from traditional factor inputs to innovation-led development. This includes rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), with 433 large AI models completing regulatory filings, and DeepSeek reaching 100 million users within seven days of launch. The humanoid robotics industry has seen strong demand, while new energy vehicles (NEVs) experienced over 40% year-on-year growth in both sales and production. Coverage of 5G-Advanced (5G-A) networks extended to over 300 Chinese cities, with more than 10 million subscribers.

China’s pivot toward domestic consumption and emerging industries as core growth drivers represents a strategic adaptation to internal and external economic pressures, aiming for more sustainable, innovation-driven development. This shift is vital for long-term stability and avoiding the “middle-income trap.” Robust growth in sectors such as AI and NEVs suggests active investment in high value-added areas, recognizing that the previous investment- and export-heavy model is no longer sufficient. This transition enhances economic resilience and reduces dependence on external fluctuations.

Strong growth in high-tech manufacturing and R&D investment, alongside the rapid commercialization of scientific inventions, indicates a robust, policy-supported ecosystem aimed at fostering indigenous innovation and moving up the value chain. This reflects a deliberate strategy to ensure future economic competitiveness. The reported 9.5% increase in value-added output from major high-tech manufacturers in the first half of 2025, along with nearly 5 million valid patent applications, signals a firm commitment to translating scientific achievements into commercial products. This is not mere quantitative growth but qualitative, aimed at enhancing China’s self-driven innovation capacity.

China’s Global Economic Role: Trade, Investment, and the Belt and Road Initiative

China has become the world’s largest economy (by PPP), largest manufacturer, largest merchandise trader, and top holder of foreign exchange reserves. It is a major trade partner for many countries, including the United States. Despite trade tensions, China remains central to global supply chains, hosting 200 mature industrial clusters in sectors like electric vehicles and green energy. Asia accounts for a significant portion of China’s trade, comprising 47.8% of exports and 54.3% of imports.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, is a massive global infrastructure development strategy aimed at enhancing connectivity between China and over 150 countries and international organizations. It is a cornerstone of President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy and reflects China’s ambition for a greater leadership role in global affairs. As of early 2024, over 140 countries had joined the initiative, collectively representing about 75% of the world’s population and more than half of global GDP.

The BRI is more than an infrastructure project; it is a geopolitical and economic strategy to bolster China’s global leadership, diversify resource access, and create new markets for its industrial capacity, fundamentally reshaping global trade routes and economic integration. Its inclusion in the CCP constitution in 2017 underscores its long-term strategic nature, beyond mere commercial investment. This signals China’s ambition to reshape the global economic order to align with its interests and assert influence as a great power.

World Bank studies indicate that the BRI could increase trade flows in 155 participating countries by 4.1%, lower global trade costs by 1.1% to 2.2%, and raise GDP in developing countries in East Asia and the Pacific by an average of 2.6% to 3.9%. It could also help lift 8.7 million people out of extreme poverty and 34 million out of moderate poverty globally.

While the BRI promises significant economic and poverty-reduction benefits for participant countries, its implementation raises concerns about debt sustainability and transparency, reflecting a complex interplay of development, influence, and risk. Although some research finds no evidence that China deliberately engages in “debt trap diplomacy,” persistent concerns about debt sustainability, human rights, and environmental impact highlight the need for careful project governance. This suggests that the BRI, in pursuing economic and geopolitical goals, must balance developmental benefits with potential risks to ensure sustainable partnerships.

Key Economic Challenges and Structural Headwinds

China’s economy faces major structural challenges, including high debt levels, deflationary pressures, and population aging. Public debt has reached 100% of GDP—high for a country with China’s income level—partly due to heavy borrowing by local governments to fund real estate and infrastructure projects. The economy also suffers from entrenched deflation, with declining export and consumer prices.

High public and local government debt, combined with deflationary pressures and excess capacity, indicates deep structural imbalances where investment-driven growth has outpaced sustainable domestic demand. The fact that fiscal deficit increases are directed at local government debt restructuring rather than boosting consumption highlights that this is not just a cyclical issue but a structural one. This situation poses significant risks to financial stability and future growth, as excess capacity can exacerbate deflation and erode corporate profit margins.

Demographic transition—marked by population decline and rapid aging—poses a long-term challenge to China’s labor supply, consumer market dynamics, and social security system. The working-age population is projected to shrink by about a quarter by 2050. The former one-child policy led to accelerated aging and a sharp fertility decline. The government is responding with three-child policies, retirement age increases, elder care development, and private pension schemes. However, aging will reduce labor productivity and lower annual GDP growth by roughly 1.3 percentage points once urbanization completes around 2035.

The persistently low ratio of private consumption to GDP, despite government efforts, reflects a societal preference for high saving, driven by a limited welfare state and few alternative investment options. The absence of major consumption stimulus in 2025 and the focus on local debt support suggest structural resistance to changing this pattern. Deep systemic reforms—like pension expansion and improved public healthcare and unemployment benefits—are needed but remain only partially implemented.

Future Economic Outlook and Policy Responses

China is adopting a new growth model focused on private consumption, services, and innovation instead of investment and exports. Recent data shows China’s economy outperforming expectations. Authorities have set a 2025 growth target of “around 5%,” matching 2024’s goal. This growth is supported by robust supply-side performance, sustained global demand for Chinese goods, and industrial policies promoting self-reliance.

China’s strategic pivot toward “new high-quality productive forces” and innovation-led growth, alongside efforts to boost consumption and address structural imbalances, represents a comprehensive approach to navigating a complex global economy and ensuring long-term, high-quality development. The recognition of the “New Normal” is not mere acceptance of slower growth but a signal of strategic realignment toward a more resilient, sustainable economy. This combines structural reforms and future industry promotion to sustain growth amid internal and external challenges.

Continued state-led investment in high-tech manufacturing, even amid calls for consumption-led growth, reflects a calculated strategy where industrial policy remains central to achieving self-sufficiency and global technological leadership—potentially prolonging overcapacity in some sectors. Investments in high-tech industries like NEVs, solar panels, and service robots demonstrate a commitment to production capacity, yet risk exacerbating overcapacity if domestic or global demand lags. This underscores an ongoing tension between self-sufficiency and global tech leadership and the need for balanced economic growth.

Conclusion

China has demonstrated extraordinary resilience in its economic transformation over recent decades, evolving from a centrally planned agrarian economy into a global industrial and trade powerhouse. This shift was underpinned by “Reform and Opening-up” policies that unleashed market forces while maintaining strong state direction. However, the model that fueled rapid growth now faces major structural challenges, including high debt, deflationary pressures, and demographic shifts.

China is responding by embracing the “New Normal” and prioritizing consumption- and innovation-driven growth, supported by “new high-quality productive forces.” The Belt and Road Initiative exemplifies China’s growing ambition to reshape the global economic landscape. However, future success will depend on China’s ability to rebalance its economy, resolve structural imbalances, boost domestic consumption, and lead in technological innovation. The complex interplay among these factors will shape China’s economic path and global influence in the decades ahead.