Jiao Feng

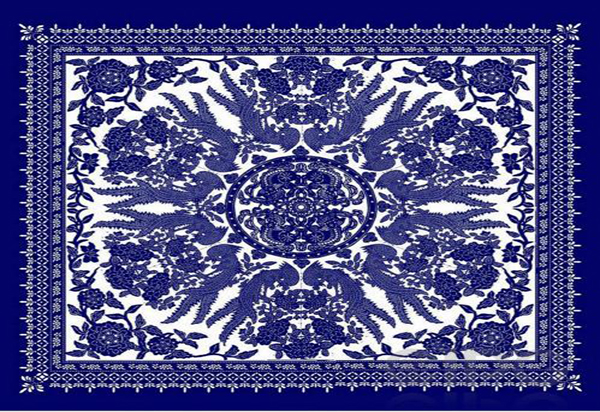

The weaving of blue spotted cotton fabric, known as “calico,” is a traditional Chinese craft that has existed for over a thousand years. Despite the simplicity of its color, this fabric has a unique elegance that reflects the aesthetics of authentic craftsmanship, the skill of the artisan who creates it, and the refined taste of its users.

The city of Nantong in Jiangsu Province is the birthplace of the blue spotted fabric weaving art in China. It is the main cotton-producing area, with many indigo plants grown to extract the distinctive blue calico dye. No home in this city is without calico blue fabrics, which are used for quilts, cushions, tablecloths, and even clothing.

Preserving Traditions

One of the leading experts in blue spotted cotton fabric is Wu Yuanxin, born in 1960 to a family working in the calico weaving craft. Wu Yuanxin mentioned that one of his most cherished memories was of his blind grandmother spinning cotton threads, and his mother weaving them. He added that he would sleep and wake up to the sound of the weaving machine. He also said that his happiest moments were when he was allowed to work in the fields with his father, helping to dye the fabric and going with him to the market to sell the products.

After his father’s health declined, Wu Yuanxin’s family faced difficult times. At the age of seventeen, he had to leave school after completing his secondary education to take on the responsibility of supporting his family.

In the 1970s, most of his peers in the rural areas worked in electrical appliance factories or semiconductor plants, but Wu chose to work in a calico fabric production factory. He said, “I was the only young worker in that factory, and I spent a lot of time learning the craft of designing and producing blue spotted cotton fabric from local artisans who were skilled at it. In my free time, I would wander around villages collecting pictures of fabric design patterns, trying to create my own designs and patterns.”

In his first year at the factory, Wu learned the basic skills. In the second year, he worked in the design and sculpture department and continued his journey in designing and producing blue spotted cotton fabric.

This ancient and beautiful hand-woven fabric remained popular until the 1950s, used in clothing and home decorations throughout China. Designs were passed down from generation to generation, and new patterns constantly emerged, keeping the blue spotted fabric in demand. However, the shift to machine printing and dyeing led to a decline in demand for calico products, forcing artisans to abandon the craft. The flow of new patterns and designs also slowed, and some even disappeared forever.

Sources of Inspiration

Wu Yuanxin was tasked with revitalizing and stimulating the designs and weaving craft of blue spotted cotton fabric. He made numerous visits to folk artisans, collecting vast amounts of information about different patterns of this folk art. In order to elevate his artistic level, he regularly visited the local cultural museum to study fine arts. He joined the Fine Arts Department at the Beijing Institute of Ceramics in 1982, where he studied decorative arts. Wu said, “At that time, only a few dyeing factory workers had studied in formal vocational schools. Although the school’s library was small, it broadened my horizons.” Wu was inspired by what he learned and came up with new patterns that greatly contributed to the development of his factory’s works.

After graduating, the school hired him, and the blue spotted cotton fabric was incorporated into the core design curriculum.

In 1987, Nantong city established an institution dedicated to handicraft tourism, headed by the calico weaving craft, and Wu Yuanxin joined it to continue his research into the art of blue spotted cotton fabric.

Wu said, “For ten years, I visited many printing and dyeing workshops. At that time, the main concern for artisans and elites in the area was to gather hidden treasures and photos of luxurious product designs. I spared no effort in collecting a special collection of my own.”

Once, Wu spent many hours traveling to a rural town to visit an elderly woman over eighty years old to obtain a classic bedspread made of blue spotted cotton fabric. He said that when he heard from a resident of Yongyang village about a rare bedspread woven from blue spotted cotton, he visited almost every house in the village until he found it. He walked miles in the rain to reach a family that had preserved blue spotted cotton fabric pillow covers for over a hundred years. The family gifted him the pieces in appreciation of his honesty and dedication.

In 1989, Wu went to the Department of Decorative Arts at the Central Academy of Craft Arts for further study on blue spotted cotton fabric. Later, he studied at the Central Academy of Fine Arts under Professor Yang Xianrang, dean of the Folk Arts College. During these two years in Beijing, Wu completed his thesis on fish designs in blue spotted cotton fabric hangings, which gained fame both domestically and internationally and won the National Handicraft Award for Tourism.

The Calico Exhibition

In 1996, the handicraft tourism institution where Wu worked faced a severe financial crisis and was merged into a hat and shoe factory. He had two choices, both unpleasant. The first was to stay at the factory designing hats, which would mean the loss of the expertise and research he had dedicated twenty years to. The second was to resign and rely on his skills to earn a living.

Years earlier, a group of Japanese traders, who recognized the cultural value of traditional crafts, offered Wu to organize an exhibition of blue spotted cotton fabric in Shanghai. A Japanese trader had taken samples of the calico works to Japan. This sparked Wu’s decision to utilize his experience and knowledge to organize an exhibition of blue spotted cotton fabric works and designs in China. It was a matter of life or death for him, so he spent all his savings and borrowed from his mother. Through his connections, he rented a space and established the “Nantong Museum of Blue Spotted Cotton Fabric.”

After a year, Wu opened the museum, which housed hundreds of items collected over twenty years. The museum also featured a dyeing workshop. During the day, Wu acted as a guide for museum visitors, explaining each piece. At night, he designed and dyed fabrics in the workshop. He traveled from Nantong to Shanghai twice a week to deliver the products, a journey that took over six hours by boat. After three years of hard work, Wu’s exhibition became self-sufficient.

In December 1999, Wu Yuanxin launched the Nantong Calico Art Exhibition at the Nationalities Cultural Palace in Beijing. This was the first time blue spotted cotton fabric was exhibited at a national level, with over five hundred pieces and photos on display, attracting large crowds of both Chinese and foreign visitors.

Wu selected three thousand pieces and photos of blue spotted cotton fabric and compiled them into a two-volume book titled The Comprehensive Collection of Blue Cotton Fabric Patterns and Designs in China, which was published in 2004, filling a gap in this field.

In 2006, the printing and dyeing of blue spotted cotton fabric was included in the first batch of intangible cultural heritage in China, solidifying Wu Yuanxin’s position as a torchbearer of this art. Some of his works won gold awards at the Third National Folk Arts Exhibition and were exhibited in the National Museum of China and the National Museum of Arts and Crafts.

Last year, Wu was invited to participate in “Chinese Culture Year” in Italy, where he exhibited around one hundred pieces of old and new blue spotted cotton fabric textiles, including children’s toys, tablecloths, and bags, in Rome, Florence, and Venice. He introduced Chinese ancient culture to foreign visitors, providing explanations on the techniques of this traditional craft.

Wu feels grateful for the honor bestowed upon the blue spotted cotton fabric art, considering it a social recognition of the efforts he has made over thirty years to research and preserve this ancient craft, which he views as his lifelong duty. Wu is devoted to advancing this beautiful aspect of folk culture.