Introduction: The Enduring Legacy of the Chinese Language

The Chinese language boasts a documented history spanning over 3,000 years, with linguistic evidence suggesting its spoken forms date back approximately 4,500 years. Oracle bone inscriptions and bronze engravings from the late Shang Dynasty (ca. 1250–1050 BCE) represent the earliest direct evidence of ancient Chinese languages. Despite this venerable lineage, the evolution of spoken Chinese has resulted in hundreds of local dialects, many of which are mutually unintelligible and as diverse as the Romance languages or even entire Indo-European language families. This profound linguistic diversity is especially pronounced in the mountainous regions of southeastern mainland China, where geographical barriers historically fostered independent linguistic development.

In response to this fragmentation, central governments have repeatedly sought to impose a standardized norm. Written Chinese, in its classical or literary form, has functioned as a vital unifying force, changing relatively little even as spoken dialects diverged, thus creating a unique diglossic relationship between spoken and written forms.

China’s linguistic landscape is marked by a deep contradiction: a single, continuous written tradition persisting for millennia coexists with hundreds of mutually unintelligible spoken varieties. The key lies in the nature of Chinese characters (hanzi), which represent morphemes (units of meaning) rather than phonemes (units of sound). This means that while pronunciation may vary greatly across regions, the written meaning remains consistent, enabling a shared literary culture and administrative unity despite spoken divergence. This unique relationship between written and spoken forms has allowed China to maintain a strong sense of cultural and political unity over centuries, despite the incredible fragmentation of its spoken linguistic landscape. It highlights how the writing system itself has become a powerful tool of cohesion.

China’s natural geography has also played a significant causal role in shaping the distribution and mutual intelligibility of spoken Chinese varieties. Data analysis indicates that Mandarin’s spread across northern China is partly due to open plains, while the “mountains and rivers of southern China… allowed for greater linguistic diversity.” One study notes that “variation is especially severe in the mountainous southeastern part of the Chinese mainland.” The mountainous terrain creates natural barriers that historically limited population movement and contact among dialects. This isolation allowed spoken forms to develop independently with less external influence, resulting in greater phonetic divergence from Middle Chinese and reduced mutual intelligibility even between neighboring communities, as seen in Fujian. Conversely, open plains facilitated greater movement and contact, leading to wider dissemination of a common spoken form (Mandarin). This underscores that language development is not purely internal but is profoundly shaped by external environmental factors, which influence national language policy and its challenges.

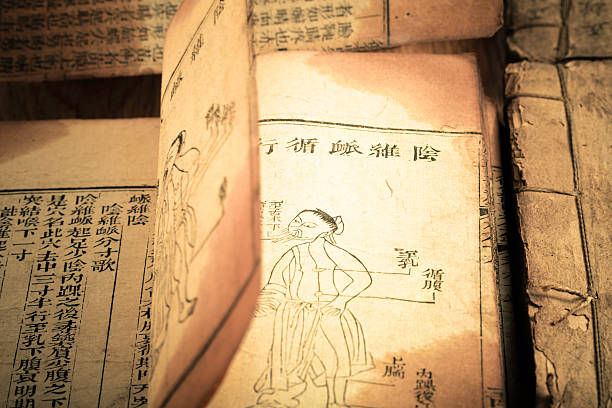

From Oracle Bones to Modern Script: The Ongoing Evolution of Written Chinese

The Chinese writing system, hanzi, is one of the oldest continuously used writing systems in the world. Its origins trace back to divination records inscribed on oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1250 BCE) and later, inscriptions on bronze artifacts. Initially, characters were ideographic or pictographic, gradually evolving through processes of abstraction and standardization for easier writing. The clerical script, which matured by early Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), obscured pictorial origins in favor of writing efficiency, leading to the regular script as the dominant style.

Complexity and Literacy: Unlike alphabetic systems, Chinese characters generally represent morphemes (units of meaning), not phonemes. This fundamental difference means achieving literacy requires memorizing thousands of distinct characters. Educated individuals typically have an active vocabulary of 3,000 to 4,000 characters, while specialists in fields such as literature or history may know 5,000 to 6,000. As of 2024, nearly 100,000 characters have been identified and included in the global Unicode Standard.

The 20th-Century Simplification Movement: The 20th century witnessed major script reform efforts aimed at promoting universal literacy and mutual comprehension. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Communist government implemented systematic character simplification, primarily by reducing stroke counts or simplifying existing forms. The principles included merging homographs, adapting connected forms, replacing complex components with simpler ones, deleting entire components, and adopting older or colloquial forms. The 1986 “General List of Simplified Chinese Characters” included 350 independent simplified characters and 132 components used to derive other characters. Although the second round of simplification in 1977 was unpopular due to unfamiliar forms and caused confusion—resulting in its formal cancellation in 1986—the 2013 “List of Standard Chinese Characters in Common Use” contains 8,105 characters, reflecting current standardized forms.

Simplifying Chinese characters in the 20th century was a wide-ranging and practical government intervention driven by the urgent need to promote universal literacy and national modernization, rather than a purely linguistic or aesthetic evolution. The immense difficulty of learning thousands of characters posed a major barrier to literacy, vital for China’s modernization. Government measures—from forming committees to issuing official lists—demonstrate a top-down strategy for national development through language engineering. The failure of the second simplification round highlights that practicality and public acceptance were key to successful reforms, showing a feedback loop between policy and social adoption. This reform reflects a broader pattern of state-led development in China, where foundational social structures are adjusted to meet national goals, even if it means altering deeply rooted cultural elements like the writing system.

Despite significant simplification efforts, the logographic nature of Chinese characters remains a substantial learning challenge, setting them apart from phonetic writing systems and impacting literacy acquisition. Studies show that Chinese characters represent morphemes (meaning) rather than sounds, unlike alphabetic systems. Research identifies literacy thresholds: 3,000–4,000 characters for general literacy, up to 6,000 for specialists. Even after simplification, the core requirement of memorizing thousands of distinct visual forms remains. This qualitative difference from learning a phonetic alphabet contributes to challenges faced by non-native learners (to be discussed in article 2) and necessitates specialized teaching approaches. It also explains why the written language historically served as a unifying force across mutually unintelligible spoken dialects, with meaning independent of pronunciation. The enduring nature of hanzi means that while simplification eased some burdens, it did not fundamentally alter the cognitive demands of Chinese literacy, preserving a unique cultural and intellectual heritage linked to its script.

A Symphony of Sounds: Exploring Major Chinese Dialects

Chinese languages are typically classified into several major groups, reflecting distinct phonological evolutions from Middle Chinese: Mandarin, Wu, Min, Xiang, Gan, Jin, Hakka, and Yue.

Mutual Intelligibility and Dialect Continuum:

These are not single languages defined by mutual intelligibility but rather dialect groups within a broader continuum. Local dialects are often mutually unintelligible, differing as much as Romance languages. This variation is particularly stark in southeastern mountainous regions, where geographic isolation has fostered greater linguistic diversity. For instance, in Fujian (home to Min dialects), even neighboring counties or villages may speak mutually unintelligible varieties.

Key Features of Major Dialects:

Mandarin (普通话):

Spoken by over 900 million people, mainly in northern China due to its open plains. Historically, Guanhua (“language of officials”) was based on the Nanjing dialect, later shifting to Beijing.Wu (吴语):

Spoken by over 85 million in Shanghai, Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu, and Anhui. Characterized by retention of voiced fricatives and complex tone sandhi (tone change patterns). Shanghai’s historical commercial importance elevated its dialect’s prominence.Min (闽语):

The most diverse branch, originating in Fujian’s mountains and eastern Guangdong. Varieties like Hokkien (Taiwanese) spread to Southeast Asia. Min cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese, suggesting a significant substratum of pre-Chinese languages. It tends to have more tonal distinctions.Xiang (湘语):

Spoken by over 38 million in Hunan and southern Hubei. Divided into “New Xiang” (Mandarin-influenced) and “Old Xiang” (retains voiced consonants). Mao Zedong’s native tongue was Xiang.Gan (赣语):

Spoken by about 48 million in Jiangxi and nearby regions. Phonetically close to Hakka; historical Han migration influenced its development. Features 4–7 tones and is culturally known for distinctive architecture and cuisine.Hakka (客家话):

Spoken by an estimated 36.8 million people, often called “guest families” due to their migratory history. Found in southern Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, and diaspora communities worldwide. Tonal, preserves nasal and stop finals, and serves as a strong cultural identity marker.Yue (粤语 – Cantonese):

Spoken by about 80 million, mainly in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, and Macau. Cantonese (Guangzhou dialect) is the prestige variety, noted for retaining final consonants and rich tonal system from Middle Chinese. Its media presence in Hong Kong has boosted its spread across Asia.

| Dialect (English/Chinese) | Geographic Areas | Approx. Speakers (millions) | Linguistic Features / Mutual Intelligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin (普通话) | North China, central/southwest regions | 900+ | Based on Beijing dialect; relatively high mutual intelligibility in the north |

| Wu (吴语) | Shanghai, Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu/Anhui | 85+ | Retains voiced fricatives; complex tone sandhi |

| Min (闽语) | Fujian, E. Guangdong, Taiwan, SE Asia | 70+ | Most diverse; not directly from Middle Chinese; many tonal distinctions |

| Xiang (湘语) | Hunan, S. Hubei | 38+ | “New” Xiang influenced by Mandarin; “Old” Xiang retains voiced consonants |

| Gan (赣语) | Jiangxi, adjacent areas | 48+ | Tonal (4–7 tones); close to Hakka; Mandarin influence near borders |

| Hakka (客家话) | SE Guangdong, SW Fujian, diaspora | 36.8+ | Tonal (8 tones); nasal/stop finals; strong identity marker |

| Yue (粤语 – Cantonese) | Guangdong, Guangxi, HK, Macau | 80+ | Tonal (8 tones); retains final consonants; popular via HK media |

Classifying these varieties as “dialects” (方言 fāngyán) despite their lack of mutual intelligibility is a sociopolitical construct reinforcing national unity and shared cultural heritage, even though linguistic evidence suggests otherwise. Linguists often argue many “dialects” are distinct languages, but official policy and popular perception in China insist on calling them dialects. This distinction underscores how language classification is intertwined with national identity and political unity, rather than mere linguistic criteria. The shared writing system (hanzi) plays a central role in this perception of unity. It highlights how language classification can be deeply entwined with national identity and ideology, demonstrating the powerful role of the state in shaping linguistic perceptions and realities.

Despite the wide influence and promotion of Standard Mandarin, regional dialects—especially those with strong cultural ties like Cantonese and Hakka—show significant resilience, acting as vital markers of local identity and enhancing in-group status. Studies indicate that while Mandarin serves as the lingua franca, continued use and cultural significance of other dialects, particularly in their native regions and diaspora, reflect deep ties to local heritage. This points to a complex diglossic relationship where Mandarin holds official status and economic utility, while regional dialects remain vibrant in informal, familial, and cultural contexts. The phrase “Hakka people believe without the Hakka dialect, there are no Hakka people” powerfully illustrates this link. It highlights the enduring strength of local cultural identity and community ties in shaping linguistic realities, showing that top-down language policies face inherent limits when confronting entrenched social practices and self-perceptions.

The Rise of Standard Mandarin (Putonghua)

Mandarin’s spread in northern China is partly attributed to open plains, unlike the linguistic diversity of the south. Historically, Guanhua (“language of officials”), initially based on the Nanjing dialect, became the dominant northern vernacular in early Qing times, later challenged by the Beijing dialect. In the Qing Dynasty, Mandarin (Guoyu – “national language”) was the official court language, with its pronunciation modeled on Beijing speech.

Establishing Putonghua: After the Qing Dynasty’s fall in 1912, the newly formed Republic of China prioritized a common language for better communication and literacy. In 1955, “Guoyu” was renamed 普通话 (Putonghua – “common speech”). Putonghua uses Beijing pronunciation, northern dialects as its phonological base, and modern vernacular written Chinese as its grammatical standard.

Its Unifying Role: Putonghua is the official language of mainland China and the language of education, government, and media. It serves as a national lingua franca, intended to be understood by all Chinese people. The Chinese government actively promotes its use through education and policy, with a 2021 goal of 85% national fluency by 2025 and a long-term goal of 100%. Promotion is overseen by the State Language Commission.

Implementation Measures: These include the Putonghua Proficiency Test (PSC), often required for certain professions like broadcasting; media promotion (limiting local dialects in media, with exceptions like Cantonese in Guangdong); and national awareness weeks.

The shift from “national language” (Guoyu) to “common language” (Putonghua), and its strong promotion, reflect a deliberate government strategy to modernize, streamline, and linguistically unify the nation, thereby aiding communication, literacy, and social cohesion. It also serves as a tool of central state control over linguistic expression. The historical context shows language unification was a post-imperial project aimed at strengthening national power. Renaming the language subtly reframes top-down imposition as a functional necessity for cross-regional communication. However, strict media policies and proficiency testing reveal the underlying governmental control and instrumental view of language for economic, educational, and cultural development.

Despite decades of promotion and ambitious goals (e.g., 100% fluency by 2050), universal Putonghua mastery remains elusive, with a significant portion of the population not speaking it at home. This highlights practical challenges and the deeply rooted nature of regional linguistic identities. Even with strong governmental support, language change is slow and complex. That only 18% used Putonghua at home in 2009 reveals a gap between policy goals and linguistic reality, indicating that while Putonghua is the official language, regional dialects remain vibrant in informal and familial settings.

Conclusion

The journey through China’s linguistic landscape testifies to the dynamic interplay between historical continuity and regional diversity. The unique relationship between Chinese characters and spoken varieties has enabled remarkable continuity of written culture despite vast spoken divergence. The logographic nature of hanzi means that changes in pronunciation across dialects did not necessarily render texts unreadable, allowing for a shared literary heritage that transcends spoken boundaries. This crucial distinction from phonetic writing systems explains the resilience of the written form.

Ongoing efforts to promote Putonghua, despite challenges from regional diversity, highlight a national project of forging a unified identity in a vast and varied country. The push for a “common language” is closely linked to the concept of national unity and cultural cohesion. Thus, the linguistic landscape reflects not only historical and geographic factors but also ongoing political and social ambitions. Chinese, in its diverse forms, stands as a living testament to China’s rich history and complex cultural identity