The Chinese writing system is distinguished as the oldest continuously used writing system in the world, and by its unique style that is fundamentally different from phonetic alphabets. Chinese written symbols, known as Hanzi (漢字, “Han characters”), are graphic representations of syllables and meanings rather than letters representing individual sounds as in most of the world’s languages. The modern script connects the Chinese nation to its ancient history, as many of these characters have evolved over thousands of years and can trace their origins back to primitive drawings of objects and concepts. The Chinese script also exerted a profound influence on East Asian cultures, as Koreans, Japanese, and Vietnamese historically borrowed it for their own writing systems. In this article, we will explore the journey of Chinese writing throughout history, its cultural and social significance, as well as modern methods and tools for learning to read and write Chinese characters.

Historical Overview of Chinese Writing

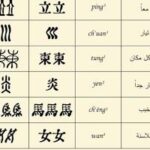

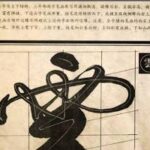

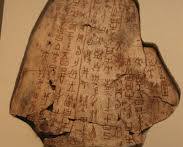

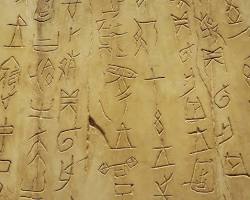

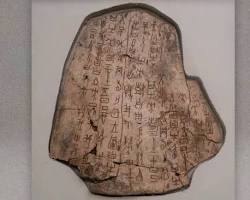

The oldest confirmed evidence of Chinese writing dates back to around the 13th century BCE during the late Shang Dynasty, when Chinese symbols were inscribed on animal bones and turtle shells for divination purposes. These inscriptions, known as oracle bone script (甲骨文, jiǎgǔwén), reveal a writing system that was already highly developed for its time, suggesting that Chinese writing began centuries earlier and started as pictorial records of objects and events. Over time, writing appeared on bronze vessels (the bronze inscriptions 金文) and then evolved into more organized forms during the Zhou Dynasty and beyond.

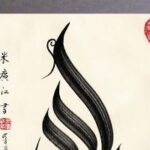

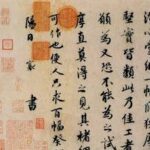

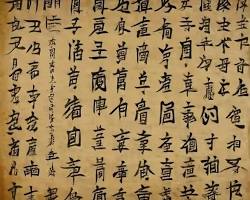

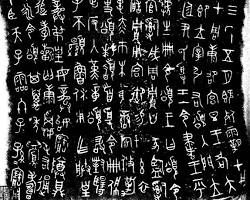

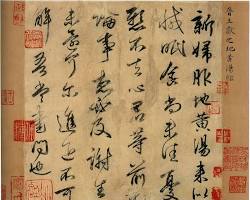

By the third century BCE, particularly under the rule of the first emperor Qin Shi Huang (221 BCE), Chinese writing underwent a significant unification. The script known as the “Small Seal” script (xiǎozhuàn, 小篆) was established as the official standard across the empire, cementing consistent forms for Chinese characters. This event is seen as a turning point at which Chinese characters became less pictorial and more abstract and regularized, coming very close to the form of Chinese characters in use today. In the following centuries, multiple calligraphic styles emerged—such as the standard script (kǎishū, 楷书) that remains in use, alongside other styles like the running script and cursive script—but all of these are stylistic variations of the same fundamental set of characters, without altering the core structure of the writing system. Thus, Chinese writing has maintained structural continuity from ancient times to the present, even as writing instruments and materials have changed.

Cultural and Social Significance of Chinese Writing

The Chinese writing system is more than just a means of communication; it is a central part of cultural identity. Generations have mastered the art of Chinese calligraphy (書法, shūfǎ) as one of the highest traditional arts, reflecting the beauty of characters and their symbolic significance. By practicing calligraphy in its various styles—from the deliberate, formal strokes to the flowing, cursive script—Chinese scholars expressed their personality and thought through their handwriting, to the point that it was said “a person’s handwriting is a mirror of their self.” Writing also served as a unifying force in Chinese civilization: classical Chinese texts could be read and understood across vast regions with different dialects, helping to preserve cultural and linguistic unity despite internal linguistic diversity.

The influence of Chinese writing spread historically beyond China’s borders. For many centuries, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam all adopted Chinese characters in their writing systems, with Buddhist scriptures, governmental documents, and classical literature recorded in those characters. Classical Chinese continued to be used as the formal written language in these countries up through the 19th century (and in Vietnam into the early 20th century). Over time, each nation developed its own writing system (for example, the Hangul alphabet in 15th-century Korea, the kana syllabaries derived from Chinese characters in Japan, and the derivative Chữ Nôm characters in Vietnam), yet Chinese characters remained present: Japanese is still written with a mix of kanji (Chinese characters) and kana scripts, and Hanja (Chinese characters) continued to be used in Korea for certain purposes up to the 20th century. In this way, the Chinese script transcended its homeland to become part of the shared cultural heritage of East Asia.

Modern Chinese Writing System: Traditional vs. Simplified

Traditional Chinese communities (such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau) have preserved use of the older set of characters, known as traditional characters (繁體字, fántǐzì), in their original forms. By contrast, the mainland Chinese government introduced a series of official modifications to many characters in the 1950s, aimed at making them easier to learn and improving literacy. This new set became known as simplified characters (简体字, jiǎntǐzì). Both sets of characters—traditional and simplified—represent the same words and meanings but have different written forms. For example, 龍 (“dragon”) in traditional is written 龙 in simplified, and 學 (“learn”) becomes 学, and so on. The People’s Republic of China has used simplified characters exclusively since the 1960s, and Singapore and Malaysia have adopted them as well, whereas Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities continue to use traditional characters in books, newspapers, and publications.

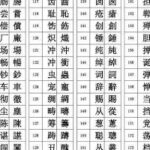

It is noted that the total number of Chinese characters throughout history exceeds 50,000 symbols, though the vast majority are no longer used in everyday life. In modern usage, knowing about 2,000 to 3,000 characters is sufficient to read most texts; studies estimate that a person familiar with this many characters can understand roughly 97%–99% of contemporary Chinese writing, which makes it an approximate threshold for literacy in the language. Educated individuals and specialists may command a larger inventory (perhaps 6,000–8,000 characters). On the other hand, the dominance of digital typing and computer input methods has led to a decline in the ability to hand-write certain characters among the younger generations; writers rely on entering words phonetically with Pinyin and then choosing the correct character from a list on the screen, without needing to recall all the details of its strokes from memory.

Learning Chinese Characters: Challenges and Tools

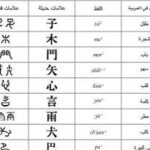

Learning to read and write Chinese characters is a unique challenge for beginners, as it requires memorizing the shapes of a large number of complex symbols. However, there are approaches that make this task more manageable. One key is to understand character components, known as radicals (部首, bùshǒu) — graphical elements that recur in many characters and suggest a certain meaning or pronunciation. Breaking a character down into its fundamental parts and learning the correct stroke order (the sequence of drawing each stroke) helps imprint its form in memory. Learners also employ mnemonic strategies to remember characters, such as linking a character’s shape to a story or a visual image. In the modern era, powerful digital tools are available for learning characters: apps and software that use spaced repetition techniques to help students effectively memorize and recall symbols (examples include applications like Skritter, Anki, and others). Regular practice writing characters by hand is also recommended—at least for a time—to grasp their structure and stroke flow, in addition to practicing calligraphy to enhance a learner’s precision and patience.

The Chinese writing system is an astonishing blend of antiquity and adaptability; it is at once a living witness to an ancient civilization and a modern writing tool that adapts to the digital age. Although learners initially face difficulty in absorbing thousands of symbols, mastering these characters opens a window onto a different way of thinking and to literary and artistic treasures that are hard to find elsewhere. Chinese writing is not just a means of recording words, but also an art, a heritage, and an identity. As the Chinese language continues to spread globally, this unique script remains a cultural link connecting the past with the present, and a bridge through which millions communicate without needing to translate spoken words.